Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

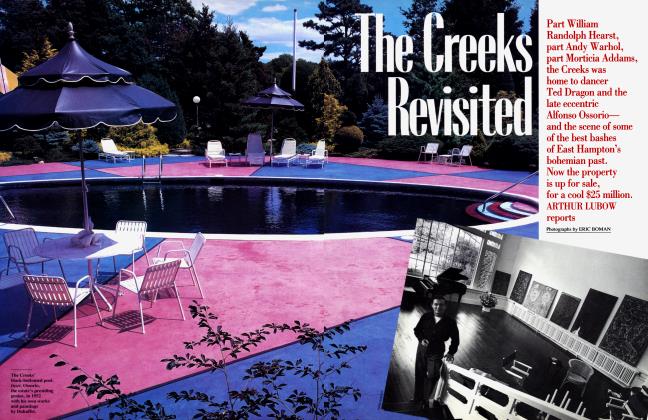

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowManic Zanuck

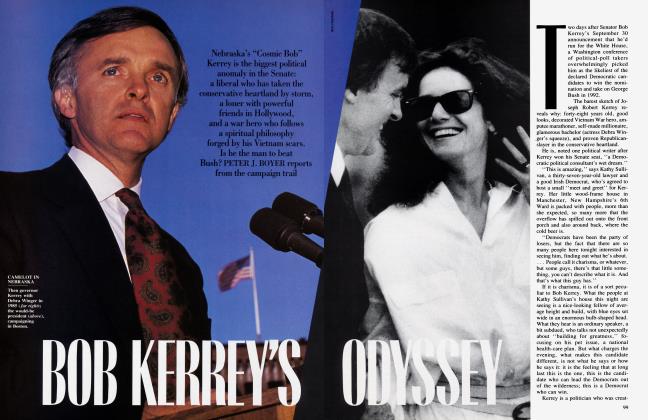

What producer Lili Zanuck (Cocoon, Driving Miss Daisy) wants, she gets. But only after a major battle. Why? Because in Hollywood, if a woman is smart and successful, she is considered the t-word, when, as Zanuck knows, it's really all about having guts. LYNN HIRSCHBERG reports as Zanuck makes her directorial debut with Rush

LYNN HIRSCHBERG

She doesn't like the word. In fact, she doesn't think it fits, even though her mother thinks it does. And yet, ten minutes with Lili Fini Zanuck and one impression lingers: she is tough. Meaning, from the jump, Lili is nononsense, straight-ahead, determined. "I'm a bottom-line kind of dame,'' she explains, carefully avoiding the dread t-word. "I don't manipulate anyone and I don't like to be manipulated. But tough. . .1 don't think of myself that way.''

At the moment (a Sunday, early November, Los Angeles), she is illustrating her point of view at a photo session. These pictures are being taken to promote Rush, a remarkable film starring Jason Patric and Jennifer Jason Leigh as two undercover narcotics agents who become addicts in the line of duty. In a spectacular, sure-handed debut, Lili directed the film, which is dark and uncompromising and, not surprisingly, quite tough. Having co-produced Cocoon and Driving Miss Daisy, which won the Academy Award for best picture of 1989, Lili is quite familiar with the world of publicity. She knows exactly what she wants and, more im-

portant, what she doesn't. In a land of insecurity and fear, Lili is very certain.

"I will not wear this dress,'' Lili says now, going through a rack of designer frocks that the photographer's stylist has assembled. She's wearing an oversize yellow T-shirt and sweatpants, and her long blond hair is swept up on top of her head in large rollers. At first glance, she has the look of the quintessential all-American high-school cheerleader (which she wasn't), but her voice, which is rather harsh and gravelly and has an indeterminate but clearly southernish accent, messes with the image. "If you just heard the voice, you might not want to meet the person," Lili's husband, Dick Zanuck, once told her. But, actually, the voice is a welcome counterpoint—it's direct, a surprise.

Lili holds up a low-cut black dress with a large feathery flower on each breast. "No way," she says. She plows through the rack—discarding an iridescent silver ensemble, a celadon taffeta coat, and a pleated red silk dress in favor of a long black velvet jacket with a handkerchief hem. "This will be O.K.," she says to the photographer. "But I really would have liked to do a Cecil B. DeMille thing. Or a clown—I would have dressed up as a clown. ' ' The photographer looks incredulous but bemused, not sure if she's kidding. "All-the-way artificial is interesting to me," says Lili. "Halfway isn't."

"When I met Lili," says Richard , "she struck me as a real ball-breaker."

She ponders the black velvet a minute. "What do you think?" she asks the photographer. "I'm a fickle woman," she adds. "You better decide right away." Lili is smiling. "You'll look great in that," he says definitively. "Yeah?" she says, suddenly a bit ambivalent. "This is exactly what William Wyler wore when he was photographed. To be a director now, you need to have good legs." The photographer smiles. "You're a fun guy," he says. Lili laughs. "I mean, girl," he corrects himself. "You're a fun girl."

hen I met Lili," Richard Zanuck is saying, "she struck me, at that time, as a real ballbreaker." Zanuck grins. "She's mellowed since then." He pauses—unlike his wife, he chooses his words carefully, although, like her he is surprisingly frank. At fifty-seven, Zanuck is quite tan and very fit—he runs five miles nearly every day. The exercise is only

part of it—Zanuck also runs at 5:30 A.M. because he likes "the way it sets up the day." Like Lili, he is driven; he thrives on work. "Because he is not flamboyant, people underestimate what a great producer Dick is," says an admiring rival. "He's had Oscars and big box office. Very few producers can say that."

"My Achilles is bothering me and I didn't run this morning," says Zanuck, sipping tea in the coffee shop of the Omni Hotel in Charleston, South Carolina. He and Lili are living in a beautiful rented house by the water while Rich in Love, the latest Zanuck Company movie, shoots nearby. This one has been more Dick's baby than Lili's—when filming began, she was still doing postproduction in California on Rush, which is scheduled to open nationwide in January. "In thirteen years of marriage we never spent a night apart," he says. "And then during Rush, David Brown and I received the Irving Thalberg award at the Academy Awards ceremony. Lili was shooting in Houston and couldn't get away. She watched it on TV. That broke the spell—thirteen years!"

Breaking the spell on that particular evening, March 25, 1991, the night of the Oscars, seems an odd twist of fate. Until Lili, David Brown and Zanuck had been partners—in fact, theirs had been the only marriage that had lasted.

"When I met Lili, I had had these two nine-year marriages and the last thing I wanted to do was get involved again," says Zanuck, warming to the topic of their barely four-month courtship. "And she seemed very tough. I was used to a different kind of lady—more demure. And in those other relationships, everything would revolve around me, which is probably why those marriages failed. This is a girl who knew what she wanted and wasn't afraid to speak her piece. So my warning signals went off."

It was 1978. Zanuck was a forty-three-year-old secondgeneration Hollywood mogul with two daughters from his first marriage and two sons from his second. Lili, twentyfour, was working as an office manager for Carnation. The daughter of a Greek mother and an Italian-American father, Lili was named after her maternal grandmother, who at age twenty-nine was killed by the Nazis. Her father, who was in the U.S. Air Force and stationed overseas, insisted that Lili be bom in America. "For only one reason," she says. "So that I could be president of the United States."

The family moved constantly, first living in Europe and then settling briefly in Florida when Lili was thirteen. She attended parochial school and, after a brief stint at college and a ninety-day marriage, decided to seek her fortune in Los Angeles. "I didn't have a game plan," she says. "But two things always motivate me: one, I don't like to be bored, and, two, I really hear the clock of life ticking. I don't feel I have this endless amount of time to live my life. I have a somewhat distorted view of loss and impending doom. I think that's because when I was twenty-one I had a very bad car accident. I was just sitting in the car talking and then I wasn't. I was hurt very badly and it took about a year for me to recover, and when I got a clean bill of health I moved to L.A."

Zanuck's father, Darryl, was Hollywood's last true tycoon, and little "Dickie," his only son, grew up selling Saturday Evening Posts and playing hide-and-seek on the Twentieth Century Fox lot, the studio his father built. At the age of twenty-four, Dick Zanuck produced his first film, Compulsion, and in 1962, at twenty-seven, he became the youngest production chief since Thalberg.

After his father fired him in a frenzy of paranoia and insecurity eight years later, Zanuck joined forces with Brown, a longtime friend, and together they produced critical and commercial blockbusters such as The Sting and Jaws.

Zanuck was dining with David Brown the day he first heard about Lili Fini. The late Pierre Groleau, Zanuck's weekly tennis partner and the co-owner of Ma Maison, then Hollywood's restaurant of choice, had met Lili when she and a girlfriend had begun frequenting the restaurant. Groleau proposed a blind date between her and Zanuck. "Pierre said, 'Dick, I must warn you. She's very bright,' " recalls Brown. "And for males of that era that meant she was not to be taken lightly. It meant she would have her demands. But Dick was the world's worst bachelor—he had no use for small talk and never appreciated the candy store that Hollywood is for men. He needs to be married, although this is a marriage that he never imagined."

After some initial reservations, mostly revolving around the voice ("It reminded me of Gravel Gertie"), he invited Lili to a screening at his home, and from that point on they were nearly inseparable.

Once they were married, Lili inherited an entirely new world. She became an instant mom: Zanuck had custody of his two sons, then five and six. "I lived in Dick's life then," she recalls. "Vacations were planned a year in advance. We'd go here, we'd do this, we'd eat here. It was like a machine and I effected no change for a long time." But one change did transpire almost instantly: Lili joined the Zanuck/Brown Company. "She came to see me alone at the George V hotel in Paris," Brown recalls. "She said, 'I want to work and I'm interested in films.' I then acted as an intermediary. I was her mentor and from the beginning I saw that Lili was a contender. She absorbed film lore as though she were a giant sponge. She knew every actor, every bit player in every TV show. Dick and I'd be talking about Spielberg, Redford, and Newman and she'd be talking about actors and directors on the cutting edge. She was a window on a world we no longer knew."

For two years, without pay, Lili worked her way up the ranks—from gofer to production assistant to development executive. "It was an easy thing, her working at the company," says Zanuck. "My father had given me a chance at an early age. He had this blind faith in me and I kind of projected that onto Lili. I knew that she would do a good job. And I also knew there'd be some arched eyebrows about her working with us, but that didn't bother me."

"People did talk about it," says one agent. "But that was before they met her. After you meet Lili, you quickly stop thinking about how she got the job."

Characteristically, Lili also ignored the cries of nepotism coming from the Hollywood community. "You can always slot me—as Mrs. Richard Zanuck or whatever—but that's for somebody else' s comfort, not for mine, ' ' she says. ' 'It doesn't mean that people don't jump to certain conclusions, but those conclusions are irrelevant to me. And they always were."

When, in 1980, Lili discovered the germ of the idea that became Cocoon, Zanuck/Brown was actively developing The Verdict and Neighbors. "Cocoon was so inexpensive to option," Lili says now, "that it was O.K., they let me have it." Lili now had her baby: she developed the script and, with the encouragement of Alan Ladd Jr., a friend as well as a once and future studio head, asked her husband and David Brown for a producing credit on the picture. She got it.

Like most of Lili's projects, Cocoon took a long time to set up. In those days, before E.T. and The Golden Girls, a movie about old people and aliens did not strike the studios as the least bit commercially viable. "For four years, I made the same speech in front of the same desk to three different executives at Fox," says Zanuck. "And finally, in 1984, the third guy said yes."

Cocoon went on to gross $75 million—and to provoke a fissure in the company. As Lili's power grew, Brown, who was based in New York, felt increasingly shut out. In the spring of 1988, Brown decided to leave the partnership. As he wrote in his memoir, Let Me Entertain You, "I finally found myself with two partners instead of one, and they were sleeping together. This did not work for me as well as it did for them. ' '

"I think now," says Zanuck, "that I wasn't as diplomatic about everything as I could have been. A lot of the things that David and I had been doing together for all those years I started transferring to Lili and became insensitive to David's feelings. People automatically started whispering about how Lili got rid of him, but really it was time. We had brought the partnership to its logical conclusion."

Yet the All About Eve/YoWo Ono scenarios persist even today: Lili Zanuck is still perceived by many as the woman who broke up a wonderful and hugely successful partnership. "Lili is entitled to her future," says Brown rather philosophically. "I always saw her gifts. I just didn't know what her timetable was."

The attendant gossip was very difficult for Lili to ignore; for a while, she lost the ability to distance herself from the opinions swirling around the town. "I was devastated," she admits. "And it was pretty public. It was very painful for me.

"I think everything would have been fine if I'd just learned a little slower," she continues matter-of-factly. "If I could have kept my place. After Cocoon, I started to have an identity of my own within the company. People thought I was moving too fast—nobody knows how much I was really holding back." She pauses. "But now I think, What was the alternative? I shouldn't have been holding back at all."

It's two on a Saturday afternoon and Lili and four of Rush's sound technicians are eating lunch at a fast-food restaurant that specializes in vegetarian hamburgers. "Did you see that story about the student who killed a fellow competitor and his professors because he didn't win a prize?" Lili is saying between bites of tuna-fish sandwich. "It was horrible. He shot them and then shot himself. All I kept thinking about was the Academy Awards—some screenwriter shouting, 'You put my script in turnaround!' and waving a gun." Lili laughs. "It could definitely happen," says one of the crew, and they all crack up. "Listen," Lili says, "there are times. .

But in fact, given the struggles she's gone through setting up each project, with the exception of the Cocoon sequel, Lili is remarkably free of bitterness. "Lili Zanuck fights harder to get movies made than any producer in town," says a former studio head. "On Driving Miss Daisy, she was as relentless as anyone I have ever witnessed. ' ' Daisy, the adaptation of Alfred Uhry's play, was a project David Brown had spotted even before it was produced Off Broadway. When he left the partnership, the newly formed Zanuck Company decided to make Daisy its first film.

Although it was an inexpensive film, at $12.5 million, finding a studio to back it proved almost impossible. "We had been turned down by everyone at a certain echelon, and Dick kind of bailed," Lili recalls. "At that point, he felt humiliated enough around town and he said, 'This is getting embarrassing—we're being turned down by people I've never heard of. ' He wanted to shelve the project. I could not do that."

Eventually, after the budget was knocked down to $7.5 million, her persistence paid off: they sold the foreign rights for $2.5 million to an independent producer, Jake Eberts, and Warner Bros, put up the remaining $5 million. The Academy Award for best picture and $106 million later, Driving Miss Daisy is, all things considered, the most profitable hit in the history of Warner Bros. Pictures.

"And then everyone liked it," says Lili. "You're almost resentful when they like it at that point. When we won the Golden Globes for Daisy, I looked into the audience and 1 saw all the people who had said no. And they're the same people who said no to Rush. There is no lesson that they learn."

Rush was the object of intense interest in Hollywood even as author Kim Wozencraft was still revising her novel, which is based on her experiences as an undercover cop who gets into trouble while working as a narcotics officer. (Wozencraft spent about a year in prison for falsifying evidence.) In the book, a female cop begins as an innocent, out to uphold the law, and winds up strung out on drugs and in an obsessive love affair with her partner. "I told the story to [producer] Dawn Steel," recalls Amanda Urban, Wozencraft's literary agent, "and she said, 'I'll option it now.' Dick Zanuck was calling me weekly from Atlanta, where they were filming Daisy, asking me if he could see it. [Producer] Scott Rudin was interested and so was nearly everyone else."

Somehow, the manuscript was leaked from Random House and that's when, as Urban says, "things whipped into a frenzy." When the smoke cleared, Rush had been sold to the Zanuck Company for a million dollars, a huge sum for a novel still in rough-draft form.

"1 thought it was good drama," says Zanuck. "It was different and honest and very real." Robert Towne (Shampoo, Chinatown) agreed to write and direct, and Tom Cruise expressed interest in the part of Jim Raynor, the male lead. "We had a lot of meetings," Lili recalls. "Towne hasn't written a word, but there were a lot of meetings." When Days of Thunder started filming in late 1989, Towne asked for four weeks to work on that film. "We never saw him again," says Zanuck.

Pete Dexter (Paris Trout), who had written two other scripts for the Zanucks, was hired to adapt the book for the screen. "In the conversations with Pete, I found myself being very comfortable with how the story should be told," recalls Lili. "And somehow through that process, I got the idea to direct Rush."

Lili, in fact, had always longed to direct—David Brown claims she had spoken of wanting to direct Driving Miss Daisy—but she was fearful of telling even her husband about her desire. "Wanting to direct is a joke," she observes. "Who doesn't want to direct? You can't have heard as many people say, 'What I really want to do is direct,' as many years as I have and not be embarrassed. After all, when you say it aloud, the joke's on you.

Continued on page 143

Continued from page 108

"It's like 'Who does she think she is? Couldn't she leave well enough alone? Couldn't she ride on her success and produce a rrovie?' You can hear that kind of garbage. And that garbage crippled me. When I first started producing, I had nothing to lose. But after Daisy—this was the first time in my life I had something to lose.''

So she resisted telling anyone. Then one day the Zanucks were driving back from a meeting together, and "Dick said, 'The Rush script will be here in a couple of days and you should get a list of directors together,' '' Lili recalls, somewhat gleefully. "I said, 'I have an idea.' He said, 'Who?' And I said, 'Me.' We were just approaching my car and I got out because I didn't want to hear him say we had just spent a million dollars and on and on. But when I got home Dick said, 'That's a very good idea.' ''

It was now their secret—they didn't even tell Jerry Perenchio, their business partner. "We kept it between us for a number of reasons,'' says Zanuck. "Lili was a woman, Lili was a wife, and I was nervous—we had a lot of money invested in the project and I knew a wellknown director would make it easier to set up."

The Zanucks still didn't have a male lead in mind. "Then one Sunday," Lili recalls, "Dick and I went to the AMC in Century City to see a movie, and it was sold out. Victoria Principal and her husband, Dr. Harry Glassman, were coming out of the theater, and they said, 'You should go see After Dark, My Sweet, with Jason Patric. He's the greatest thing you've ever seen.' We went and there weren't two seats together, and I'm watching this movie, thinking, This guy's Raynor. And then I'm walking up the aisle and Dick goes, 'That's Raynor. ' "

They called Patric's agent, David Schiff, and set up a meeting. Patric, who has recently gained tabloid fame as the object of Julia Roberts's affections, came and stared at the floor and did not speak. At a second meeting, he was more voluble and, expressing interest in the role, wanted to know who the director was. "I told him, 'It's somebody in this room and it's not me and it's not you,' " says Zanuck, who added, " 'You're going to think that I'm just a husband who's trying to get his wife a job, but I'm not.' Jason was stunned. He felt betrayed." Patric turned them down.

"He was shocked," says Schiff. "And we were surprised." Patric's resistance to Lili neatly mirrored the response of the town: "Think about it," says one agent. "Dick paid a million dollars so his wife could direct—who else would make that deal? First there was Robert Towne and Tom Cruise; now it's Lili Zanuck and a bunch of unknowns? For those who want to exploit vulnerability, and God knows that's most people in Hollywood, this was a wide-open one."

But Lili wanted Patric. "We told him, 'The part is yours. You've said no, we haven't.' " Eventually, "after hours upon hours and days upon days," according to his agent, Patric came around. (It was a smart move: he is terrific in the film— edgy and tortured and, finally, very moving.) Once again, Lili's persistence paid off—she got her man.

With two little-known leads, a firsttime director, and a projected budget of $17 million, the Zanucks went looking for a studio. Warner Bros, said no, too dark. Paramount said no, too expensive and too dark. Then, at MGM, Alan Ladd Jr. said yes. The Zanuck Company subsequently signed an overall distribution deal with MGM-Pathe. "With Rush, I never really got discouraged," Lili says now. "A long time ago, I learned not to personalize these things."

Lili is cross. She plops down on the couch in the back of the studio where Rush's sound is being corrected, and stares for a moment, collecting her thoughts. "On the way over here, an interviewer called me in the car," she says finally. "She asked me how Dick and I directed the movie."

ith Rush, I never really got discouraged, Liii says. "A long time ago, I learned not to personalize these things."

Lili looks up at the blank screen. Her resolve—her stubborn refusal to listen to Hollywood naysayers and skeptics—is cracking. Since the first dailies began arriving from Houston, Rush has been the subject of much interest—and sniping. "First you heard the movie was great," says one agent. "In the beginning, everyone is always nice—Jason is great, Jennifer is great, and Lili is doing a terrific job. But there's too much jealousy for that to last, and, besides, Lili is a woman and a wife. So then you heard people saying, 'Well, the movie's great because she had a good crew, a great director of photography'—the conventional wisdom being that a chimp could direct a great film with a great D.P. In Hollywood, people love to believe the worst."

"Since the movie is good, they credit the crew," says Tracey Jacobs, Lili's agent. "But if the movie was bad, they would blame Lili. If you're a woman in Hollywood, you're damned if you do and damned if you don't."

"I've heard all that," says Lili, sounding unusually exasperated and angry. "First, Dick was dragging his armpiece along with him, and now I'm this femme fatale. I went from being a bimbo to Medusa." She smiles grimly at the image. "What do they think—that I somehow coerced Dick into letting me direct? That I put something in his tea? And now if I work with another producer, people will say I was just using him to get ahead. Think about it—if you get a promotion, does that mean your relationship is over?"

Rush starts to roll. The credits come up against a long Orson Welles-ian shot that follows the main villain, played by Gregg Allman, through his honky-tonk bar. "You know," Lili whispers, "I opted not to call this 'A Lili Fini Zanuck Film.' I thought that was pretentious." She gets up to join her guys at the board. "Now, with all that's happening, maybe I should have."

The Zanuck Company offices are in Beverly Hills, on the ground floor of a small office building. Lili's office is down a longish hall and to the right, while her husband's office is at the other end. They often work all day without seeing each other, apprising each other of the day's events over dinner.

It's after lunch on a Monday and Lili has just met with her decorator. She and Dick have almost completed their "dream house," which they are building on four acres, high up above the Beverly Hills Hotel. Lili has been through this process before—she supervised the construction of their home in Sun Valley—but this experience has been a nightmare. "It'll be ready by Christmas," Dick says optimistically. "It'll be ready by Valentine's Day," Lili says with resolve.

They have been building the house for about three years, since shortly after they sold the Santa Monica beach house that Darryl F. Zanuck built. As usual, there was much gossip about Lili's having manipulated her husband to suit her own ends. "It wasn't the ancestral home or anything," she says. "What do people think—I was planning it on our honeymoon and just waited eleven years? People sell houses. People move. The kids were grown up and out of there. It was time to leave."

The new house is far from finished. "There's no bedroom," Zanuck notes. ''There's no kitchen. But the tennis court is finished. If I made a movie like this, it would be the last one I ever made." This week, Lili and Dick have been living in the guesthouse. "My poor husband," Lili says. "Every day, a hundred guys come pounding."

Not that any of this seems to really bother Lili—she's building the house and so of course it will get done. "She goes out and gets it," says a friend. "In a man, that would be admired. In a woman, it's seen as terrifying." Today, as with nearly any other day, Lili has too much to do. The holiday season is nearly here and Lili does all the corporate Christmas shopping herself, as well as buying presents for Dick's four children and his six grandchildren. There is press on Rush to take care of and then there's packing for a trip back to South Carolina—she has to get some coats and sweaters out of storage. But Lili thrives on pressure. This is, after all, a woman who believes the headaches she gets on Sundays are because she has no work to do, no errands to run: "My doctor told me that during the week I get an adrenal rush to the brain and on Sundays, when I'm not working, my brain misses that rush." Not surprisingly, she's not wild about vacations. "I do well for about three days and then I don't like it," she says earnestly, sitting in a straight-backed chair in her office.

The phone is ringing in the outer office, but Lili's assistant, Danuta Stuart, is holding all calls unless Eric Clapton phones. He did the music for Rush, and Lili needs to discuss the video for the movie, which is to be filmed next week in London. "I must have made seventy phone calls to get Eric Clapton for this movie," she says. "I had no second choice. I was so sure he was going to do it, I wouldn't think of a second choice. I think if you start to think about someone else, you're not fighting hard enough for what you really want. You're already starting to get comfortable. You won't stay on your course."

In the end, as seems to happen most of the time with Lili, she realized her dream. Around the office is photographic proof of those triumphs: pictures of Dick running in the surf, Dick and Lili and Jack and Warren the night Driving Miss Daisy won best picture, a photo of the cast of Cocoon. A pile of thirty-odd scripts is stacked on a coffee table, a testament to the buzz on Rush.

"I haven't read anything I like," she says, though it's rumored she is interested in directing The Remains of the Day, from the Kazuo Ishiguro novel about an English butler and his loyalty to his former employer, a Nazi sympathizer. Mike Nichols has been slated to direct the movie, but, with Lili on the case, anything is possible.

She stares at the pile of scripts, looking somewhat frustrated. "What people don't realize is that I would chuck the whole motion-picture business tomorrow. But then there would be a problem with what to do with my time." Lili smiles. "You know, we have this house in Sun Valley," she says. "I could always run for mayor."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now