Emancipation Proclamation

| Regarding the Status of Slaves in States Engaged in Rebellion Against the United States | |

| Summary | |

|---|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal 16th President of the United States

Tenure Speeches and works

Legacy  |

||

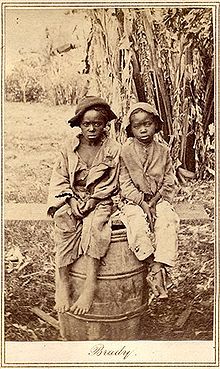

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95,[2][3] was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the effect of changing the legal status of more than 3.5 million enslaved African Americans in the secessionist Confederate states from enslaved to free. As soon as slaves escaped the control of their enslavers, either by fleeing to Union lines or through the advance of federal troops, they were permanently free. In addition, the Proclamation allowed for former slaves to "be received into the armed service of the United States". The Emancipation Proclamation played a significant part in the end of slavery in the United States.

On September 22, 1862, Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.[4] Its third paragraph begins:

That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the final Emancipation Proclamation.[5] It stated:

I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief, of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion, do ... order and designate as the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof respectively, are this day in rebellion, against the United States, the following, to wit:

Lincoln then listed the ten states[6] still in rebellion, excluding parts of states under Union control, and continued:

I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free. ... [S]uch persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States. ... And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

The proclamation provided that the executive branch, including the Army and Navy, "will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons".[7] Even though it excluded states not in rebellion, as well as parts of Louisiana and Virginia under Union control,[8] it still applied to more than 3.5 million of the 4 million enslaved people in the country. Around 25,000 to 75,000 were immediately emancipated in those regions of the Confederacy where the US Army was already in place. It could not be enforced in the areas still in rebellion,[8] but, as the Union army took control of Confederate regions, the Proclamation provided the legal framework for the liberation of more than three and a half million enslaved people in those regions by the end of the war. The Emancipation Proclamation outraged white Southerners and their sympathizers, who saw it as the beginning of a race war. It energized abolitionists, and undermined those Europeans who wanted to intervene to help the Confederacy.[9] The Proclamation lifted the spirits of African Americans, both free and enslaved. It encouraged many to escape from slavery and flee toward Union lines, where many joined the Union Army.[10] The Emancipation Proclamation became a historic document because it "would redefine the Civil War, turning it [for the North] from a struggle [solely] to preserve the Union to one [also] focused on ending slavery, and set a decisive course for how the nation would be reshaped after that historic conflict."[11]

The Emancipation Proclamation was never challenged in court. To ensure the abolition of slavery in all of the U.S., Lincoln also insisted that Reconstruction plans for Southern states require them to enact laws abolishing slavery (which occurred during the war in Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana); Lincoln encouraged border states to adopt abolition (which occurred during the war in Maryland, Missouri, and West Virginia) and pushed for passage of the 13th Amendment. The Senate passed the 13th Amendment by the necessary two-thirds vote on April 8, 1864; the House of Representatives did so on January 31, 1865; and the required three-fourths of the states ratified it on December 6, 1865. The amendment made slavery and involuntary servitude unconstitutional, "except as a punishment for a crime".[12]

Authority

The United States Constitution of 1787 did not use the word "slavery" but included several provisions about unfree persons. The Three-Fifths Compromise (in Article I, Section 2) allocated congressional representation based "on the whole Number of free Persons" and "three-fifths of all other Persons".[13] Under the Fugitive Slave Clause (Article IV, Section 2), "No person held to Service or Labour in one State" would become legally free by escaping to another. Article I, Section 9 allowed Congress to pass legislation to outlaw the "Importation of Persons", but not until 1808.[14] However, for purposes of the Fifth Amendment—which states, "No person shall ... be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law"—slaves were understood to be property.[15] Although abolitionists used the Fifth Amendment to argue against slavery, it was made part of the legal basis for treating slaves as property by Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857).[16] Slavery was also supported in law and in practice by a pervasive culture of white supremacy.[17] Nonetheless, between 1777 and 1804, every Northern state provided for the immediate or gradual abolition of slavery. No Southern state did so, and the slave population of the South continued to grow, peaking at almost four million people at the beginning of the Civil War, when most slave states sought to break away from the United States.[18]

Lincoln understood that the federal government's power to end slavery in peacetime was limited by the Constitution, which, before 1865, committed the issue to individual states.[19] During the Civil War, however, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation under his authority as "Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy" under Article II, section 2 of the United States Constitution.[20] As such, in the Emancipation Proclamation he claimed to have the authority to free persons held as slaves in those states that were in rebellion "as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion". In the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln said "attention is hereby called" to two 1862 statutes, namely "An Act to Make an Additional Article of War" and the Confiscation Act of 1862, but he didn't mention any statute in the Final Emancipation Proclamation and, in any event, the source of his authority to issue the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation and the Final Emancipation Proclamation was his "joint capacity as President and Commander-in-Chief".[21] Lincoln therefore did not have such authority over the four border slave-holding states that were not in rebellion—Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland and Delaware—so those states were not named in the Proclamation.[23] The fifth border jurisdiction, West Virginia, where slavery remained legal but was in the process of being abolished, was, in January 1863, still part of the legally recognized "reorganized" state of Virginia, based in Alexandria, which was in the Union (as opposed to the Confederate state of Virginia, based in Richmond).

Coverage

The Emancipation Proclamation applied in the ten states that were still in rebellion on January 1, 1863, but it did not cover the nearly 500,000 slaves in the slaveholding border states (Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware) or in parts of Virginia and Louisiana that were no longer in rebellion. Those slaves were freed by later state and federal actions.[24] The areas covered were "Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana (except the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James, Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the city of New Orleans), Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkley, Accomac, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Ann, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth)."[25]

The state of Tennessee had already mostly returned to Union control, under a recognized Union government, so it was not named and was exempted. Virginia was named, but exemptions were specified for the 48 counties then in the process of forming the new state of West Virginia, and seven additional counties and two cities in the Union-controlled Tidewater region of Virginia.[26] Also specifically exempted were New Orleans and 13 named parishes of Louisiana, which were mostly under federal control at the time of the Emancipation Proclamation. These exemptions left unemancipated an additional 300,000 slaves.[27]

The Emancipation Proclamation has been ridiculed, notably by Richard Hofstadter, who wrote that it "had all the moral grandeur of a bill of lading" and "declared free all slaves ... precisely where its effect could not reach".[28][29] Disagreeing with Hofstadter, William W. Freehling wrote that Lincoln's asserting his power as Commander-in-Chief to issue the proclamation "reads not like an entrepreneur's bill for past services but like a warrior's brandishing of a new weapon".[30]

The Emancipation Proclamation resulted in the emancipation of a substantial percentage of the slaves in the Confederate states as the Union armies advanced through the South and slaves escaped to Union lines, or slave owners fled, leaving slaves behind. The Emancipation Proclamation also committed the Union to ending slavery in addition to preserving the Union.

Although the Emancipation Proclamation resulted in the gradual freeing of most slaves, it did not make slavery illegal. Of the states that were exempted from the Emancipation Proclamation, Maryland,[31] Missouri,[32] Tennessee,[33] and West Virginia[34] prohibited slavery before the war ended. In 1863, President Lincoln proposed a moderate plan for the Reconstruction of the captured Confederate State of Louisiana.[35] Only 10 percent of the state's electorate had to take the loyalty oath. The state was also required to accept the Emancipation Proclamation and abolish slavery in its new constitution. By December 1864, the Lincoln plan abolishing slavery had been enacted not only in Louisiana, but also in Arkansas and Tennessee.[36][37] In Kentucky, Union Army commanders relied on the proclamation's offer of freedom to slaves who enrolled in the Army and provided freedom for an enrollee's entire family; for this and other reasons, the number of slaves in the state fell by more than 70 percent during the war.[38] However, in Delaware[39] and Kentucky,[40] slavery continued to be legal until December 18, 1865, when the Thirteenth Amendment went into effect.

Background

Military action prior to emancipation

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 required individuals to return runaway slaves to their owners. During the war, in May 1861, Union general Benjamin Butler declared that three slaves who escaped to Union lines were contraband of war, and accordingly he refused to return them, saying to a man who sought their return, "I am under no constitutional obligations to a foreign country, which Virginia now claims to be".[41] On May 30, after a cabinet meeting called by President Lincoln, "Simon Cameron, the secretary of war, telegraphed Butler to inform him that his contraband policy 'is approved.'"[42] This decision was controversial because it could have been taken to imply recognition of the Confederacy as a separate, independent sovereign state under international law, a notion that Lincoln steadfastly denied. In addition, as contraband, these people were legally designated as "property" when they crossed Union lines and their ultimate status was uncertain.[43]

Governmental action toward emancipation

![A dark-haired, bearded, middle-aged man holding documents is seated among seven other men.]]](/cats-d8c4vu/upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a7/Mano_cursor.svg/10px-Mano_cursor.svg.png) Clickable image: use cursor to identify.

Clickable image: use cursor to identify.In December 1861, Lincoln sent his first annual message to Congress (the State of the Union Address, but then typically given in writing and not referred to as such). In it he praised the free labor system for respecting human rights over property rights; he endorsed legislation to address the status of contraband slaves and slaves in loyal states, possibly through buying their freedom with federal money; and he endorsed federal funding of voluntary colonization.[44][45] In January 1862, Thaddeus Stevens, the Republican leader in the House, called for total war against the rebellion to include emancipation of slaves, arguing that emancipation, by forcing the loss of enslaved labor, would ruin the rebel economy. On March 13, 1862, Congress approved an Act Prohibiting the Return of Slaves, which prohibited "All officers or persons in the military or naval service of the United States" from returning fugitive slaves to their owners.[46] Pursuant to a law signed by Lincoln, slavery was abolished in the District of Columbia on April 16, 1862, and owners were compensated.[47]

On June 19, 1862, Congress prohibited slavery in all current and future United States territories (though not in the states), and President Lincoln quickly signed the legislation. This act effectively repudiated the 1857 opinion of the Supreme Court of the United States in the Dred Scott case that Congress was powerless to regulate slavery in U.S. territories.[48][49] It also rejected the notion of popular sovereignty that had been advanced by Stephen A. Douglas as a solution to the slavery controversy, while completing the effort first legislatively proposed by Thomas Jefferson in 1784 to confine slavery within the borders of existing states.[50][51]

On August 6, 1861, the First Confiscation Act freed the slaves who were employed "against the Government and lawful authority of the United States."[52] On July 17, 1862, the Second Confiscation Act freed the slaves "within any place occupied by rebel forces and afterwards occupied by forces of the United States."[53] The Second Confiscation Act, unlike the First Confiscation Act, explicitly provided that all slaves covered by it would be permanently freed, stating in section 10 that "all slaves of persons who shall hereafter be engaged in rebellion against the government of the United States, or who shall in any way give aid or comfort thereto, escaping from such persons and taking refuge within the lines of the army; and all slaves captured from such persons or deserted by them and coming under the control of the government of the United States; and all slaves of such person found on [or] being within any place occupied by rebel forces and afterwards occupied by the forces of the United States, shall be deemed captives of war, and shall be forever free of their servitude, and not again held as slaves."[54] However, Lincoln's position continued to be that, although Congress lacked the power to free the slaves in rebel-held states, he, as commander in chief, could do so if he deemed it a proper military measure.[55] By this time, in the summer of 1862, Lincoln had drafted the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which he issued on September 22, 1862. It declared that, on January 1, 1863, he would free the slaves in states still in rebellion.[56]

Public opinion of emancipation

Abolitionists had long been urging Lincoln to free all slaves. In the summer of 1862, Republican editor Horace Greeley of the highly influential New-York Tribune wrote a famous editorial entitled "The Prayer of Twenty Millions" demanding a more aggressive attack on the Confederacy and faster emancipation of the slaves: "On the face of this wide earth, Mr. President, there is not one ... intelligent champion of the Union cause who does not feel ... that the rebellion, if crushed tomorrow, would be renewed if slavery were left in full vigor and that every hour of deference to slavery is an hour of added and deepened peril to the Union."[57] Lincoln responded in his open letter to Horace Greeley of August 22, 1862:

If there be those who would not save the Union, unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union.... I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty; and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men everywhere could be free.[58]

Lincoln scholar Harold Holzer wrote about Lincoln's letter: "Unknown to Greeley, Lincoln composed this after he had already drafted a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which he had determined to issue after the next Union military victory. Therefore, this letter, was in truth, an attempt to position the impending announcement in terms of saving the Union, not freeing slaves as a humanitarian gesture. It was one of Lincoln's most skillful public relations efforts, even if it has cast longstanding doubt on his sincerity as a liberator."[56] Historian Richard Striner argues that "for years" Lincoln's letter has been misread as "Lincoln only wanted to save the Union."[59] However, within the context of Lincoln's entire career and pronouncements on slavery this interpretation is wrong, according to Striner. Rather, Lincoln was softening the strong Northern white supremacist opposition to his imminent emancipation by tying it to the cause of the Union. This opposition would fight for the Union but not to end slavery, so Lincoln gave them the means and motivation to do both, at the same time.[59] In effect, then, Lincoln may have already chosen the third option he mentioned to Greeley: "freeing some and leaving others alone"; that is, freeing slaves in the states still in rebellion on January 1, 1863, but leaving enslaved those in the border states and Union-occupied areas.

Nevertheless, in the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation itself, Lincoln said that he would recommend to Congress that it compensate states that "adopt, immediate, or gradual abolishment of slavery". In addition, during the hundred days between September 22, 1862, when he issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, and January 1, 1863, when he issued the Final Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln took actions that suggest that he continued to consider the first option he mentioned to Greeley — saving the Union without freeing any slave — a possibility. Historian William W. Freehling wrote, "From mid-October to mid-November 1862, he sent personal envoys to Louisiana, Tennessee, and Arkansas".[60][61] Each of these envoys carried with him a letter from Lincoln stating that if the people of their state desired "to avoid the unsatisfactory" terms of the Final Emancipation Proclamation "and to have peace again upon the old terms" (i.e., with slavery intact), they should rally "the largest number of the people possible" to vote in "elections of members to the Congress of the United States ... friendly to their object".[62] Later, in his Annual Message to Congress of December 1, 1862, Lincoln proposed an amendment to the U.S. Constitution providing that any state that abolished slavery before January 1, 1900, would receive compensation from the United States in the form of interest-bearing U.S. bonds. Adoption of this amendment, in theory, could have ended the war without ever permanently ending slavery, because the amendment provided, "Any State having received bonds ... and afterwards reintroducing or tolerating slavery therein, shall refund to the United States the bonds so received, or the value thereof, and all interest paid thereon".[63]

In his 2014 book, Lincoln's Gamble, journalist and historian Todd Brewster asserted that Lincoln's desire to reassert the saving of the Union as his sole war goal was, in fact, crucial to his claim of legal authority for emancipation. Since slavery was protected by the Constitution, the only way that he could free the slaves was as a tactic of war—not as the mission itself.[64] But that carried the risk that when the war ended, so would the justification for freeing the slaves. Late in 1862, Lincoln asked his Attorney General, Edward Bates, for an opinion as to whether slaves freed through a war-related proclamation of emancipation could be re-enslaved once the war was over. Bates had to work through the language of the Dred Scott decision to arrive at an answer, but he finally concluded that they could indeed remain free. Still, a complete end to slavery would require a constitutional amendment.[65]

Conflicting advice as to whether to free the slaves was presented to Lincoln in public and private. Thomas Nast, a cartoon artist during the Civil War and the late 1800s considered "Father of the American Cartoon", composed many works, including a two-sided spread that showed the transition from slavery into civilization after President Lincoln signed the Proclamation. Nast believed in equal opportunity and equality for all people, including enslaved Africans or free blacks. A mass rally in Chicago on September 7, 1862, demanded immediate and universal emancipation of slaves. A delegation headed by William W. Patton met the president at the White House on September 13. Lincoln had declared in peacetime that he had no constitutional authority to free the slaves. Even used as a war power, emancipation was a risky political act. Public opinion as a whole was against it.[66] There would be strong opposition among Copperhead Democrats and an uncertain reaction from loyal border states. Delaware and Maryland already had a high percentage of free blacks: 91.2% and 49.7%, respectively, in 1860.[67]

Drafting and issuance of the proclamation

Lincoln first discussed the proclamation with his cabinet in July 1862. He drafted his preliminary proclamation and read it to Secretary of State William Seward and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, on July 13. Seward and Welles were at first speechless, then Seward referred to possible anarchy throughout the South and resulting foreign intervention; Welles apparently said nothing. On July 22, Lincoln presented it to his entire cabinet as something he had determined to do and he asked their opinion on wording.[68] Although Secretary of War Edwin Stanton supported it, Seward advised Lincoln to issue the proclamation after a major Union victory, or else it would appear as if the Union was giving "its last shriek of retreat".[69] Walter Stahr, however, writes, "There are contemporary sources, however, that suggest others were involved in the decision to delay", and Stahr quotes them.[70]

In September 1862, the Battle of Antietam gave Lincoln the victory he needed to issue the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. In the battle, though the Union suffered heavier losses than the Confederates and General McClellan allowed the escape of Robert E. Lee's retreating troops, Union forces turned back a Confederate invasion of Maryland, eliminating more than a quarter of Lee's army in the process. This marked a turning point in the Civil War.

On September 22, 1862, five days after Antietam, and while residing at the Soldier's Home, Lincoln called his cabinet into session and issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.[71] According to Civil War historian James M. McPherson, Lincoln told cabinet members, "I made a solemn vow before God, that if General Lee was driven back from Pennsylvania, I would crown the result by the declaration of freedom to the slaves."[72][73] Lincoln had first shown an early draft of the proclamation to Vice President Hannibal Hamlin,[74] an ardent abolitionist, who was more often kept in the dark on presidential decisions. Lincoln issued the final proclamation, as he had promised in the preliminary proclamation, on January 1, 1863. Although implicitly granted authority by Congress, Lincoln used his powers as Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy to issue the proclamation "as a necessary war measure." Therefore, it was not the equivalent of a statute enacted by Congress or a constitutional amendment, because Lincoln or a subsequent president could revoke it. One week after issuing the final Proclamation, Lincoln wrote to Major General John McClernand: "After the commencement of hostilities I struggled nearly a year and a half to get along without touching the 'institution'; and when finally I conditionally determined to touch it, I gave a hundred days fair notice of my purpose, to all the States and people, within which time they could have turned it wholly aside, by simply again becoming good citizens of the United States. They chose to disregard it, and I made the peremptory proclamation on what appeared to me to be a military necessity. And being made, it must stand". Lincoln continued, however, that the states included in the proclamation could "adopt systems of apprenticeship for the colored people, conforming substantially to the most approved plans of gradual emancipation; and ... they may be nearly as well off, in this respect, as if the present trouble had not occurred". He concluded by asking McClernand not to "make this letter public".[75][76]

Initially, the Emancipation Proclamation effectively freed only a small percentage of the slaves, namely those who were behind Union lines in areas not exempted. Most slaves were still behind Confederate lines or in exempted Union-occupied areas. Secretary of State William H. Seward commented, "We show our sympathy with slavery by emancipating slaves where we cannot reach them and holding them in bondage where we can set them free." Had any slave state ended its secession attempt before January 1, 1863, it could have kept slavery, at least temporarily. The Proclamation freed the slaves only in areas of the South that were still in rebellion on January 1, 1863. But as the Union army advanced into the South, slaves fled to behind its lines, and "[s]hortly after issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, the Lincoln administration lifted the ban on enticing slaves into Union lines."[77] These events contributed to the destruction of slavery.

The Emancipation Proclamation also allowed for the enrollment of freed slaves into the United States military. During the war nearly 200,000 black men, most of them ex-slaves, joined the Union Army.[78] Their contributions were significant in winning the war. The Confederacy did not allow slaves in their army as soldiers until the last month before its defeat.[79]

Though the counties of Virginia that were soon to form West Virginia were specifically exempted from the Proclamation (Jefferson County being the only exception), a condition of the state's admittance to the Union was that its constitution provide for the gradual abolition of slavery (an immediate emancipation of all slaves was also adopted there in early 1865). Slaves in the border states of Maryland and Missouri were also emancipated by separate state action before the Civil War ended. In Maryland, a new state constitution abolishing slavery in the state went into effect on November 1, 1864. The Union-occupied counties of eastern Virginia and parishes of Louisiana, which had been exempted from the Proclamation, both adopted state constitutions that abolished slavery in April 1864.[80][81] In early 1865, Tennessee adopted an amendment to its constitution prohibiting slavery.[82][83]

Implementation

The Proclamation was issued in a preliminary version and a final version. The former, issued on September 22, 1862, was a preliminary announcement outlining the intent of the latter, which took effect 100 days later on January 1, 1863, during the second year of the Civil War. The preliminary Emancipation Proclamation was Abraham Lincoln's declaration that all slaves would be permanently freed in all areas of the Confederacy that were still in rebellion on January 1, 1863. The ten affected states were individually named in the final Emancipation Proclamation (South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina). Not included were the Union slave states of Maryland, Delaware, Missouri and Kentucky. Also not named was the state of Tennessee, in which a Union-controlled military government had already been set up, based in the capital, Nashville. Specific exemptions were stated for areas also under Union control on January 1, 1863, namely 48 counties that would soon become West Virginia, seven other named counties of Virginia including Berkeley and Hampshire counties, which were soon added to West Virginia, New Orleans and 13 named parishes nearby.[84]

Union-occupied areas of the Confederate states where the proclamation was put into immediate effect by local commanders included Winchester, Virginia,[85] Corinth, Mississippi,[86] the Sea Islands along the coasts of the Carolinas and Georgia,[87] Key West, Florida,[88] and Port Royal, South Carolina.[89]

Immediate impact

On New Year's Eve in 1862, African Americans – enslaved and free – gathered across the United States to hold Watch Night ceremonies for "Freedom's Eve", looking toward the stroke of midnight and the promised fulfillment of the Proclamation.[91] It has been inaccurately claimed that the Emancipation Proclamation did not free a single slave;[92] historian Lerone Bennett Jr. alleged that the proclamation was a hoax deliberately designed not to free any slaves.[93] However, as a result of the Proclamation, most slaves became free during the course of the war, beginning on the day it took effect; eyewitness accounts at places such as Hilton Head Island, South Carolina,[94] and Port Royal, South Carolina[89] record celebrations on January 1 as thousands of blacks were informed of their new legal status of freedom. "Estimates of the number of slaves freed immediately by the Emancipation Proclamation are uncertain. One contemporary estimate put the 'contraband' population of Union-occupied North Carolina at 10,000, and the Sea Islands of South Carolina also had a substantial population. Those 20,000 slaves were freed immediately by the Emancipation Proclamation."[95][96] This Union-occupied zone where freedom began at once included parts of eastern North Carolina, the Mississippi Valley, northern Alabama, the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, a large part of Arkansas, and the Sea Islands of Georgia and South Carolina.[97] Although some counties of Union-occupied Virginia were exempted from the Proclamation, the lower Shenandoah Valley and the area around Alexandria were covered.[95] Emancipation was immediately enforced as Union soldiers advanced into the Confederacy. Slaves fled their masters and were often assisted by Union soldiers.[98] On the other hand, Robert Gould Shaw wrote to his mother on September 25, 1862, "So the 'Proclamation of Emancipation' has come at last, or rather, its forerunner. I suppose you all are very much excited about it. For my part, I can't see what practical good it can do now. Wherever our army has been, there remain no slaves, and the Proclamation will not free them where we don't go." Ten days later, he wrote her again, "Don't imagine, from what I said in my last that I thought Mr. Lincoln's 'Emancipation Proclamation' not right ... but still, as a war-measure, I don't see the immediate benefit of it, ... as the slaves are sure of being free at any rate, with or without an Emancipation Act."[99]

Booker T. Washington, as a boy of 9 in Virginia, remembered the day in early 1865:[100]

As the great day drew nearer, there was more singing in the slave quarters than usual. It was bolder, had more ring, and lasted later into the night. Most of the verses of the plantation songs had some reference to freedom.... [S]ome man who seemed to be a stranger (a United States officer, I presume) made a little speech and then read a rather long paper—the Emancipation Proclamation, I think. After the reading we were told that we were all free, and could go when and where we pleased. My mother, who was standing by my side, leaned over and kissed her children, while tears of joy ran down her cheeks. She explained to us what it all meant, that this was the day for which she had been so long praying, but fearing that she would never live to see.

Runaway slaves who had escaped to Union lines had previously been held by the Union Army as "contraband of war" under the Confiscation Acts. The Sea Islands off the coast of Georgia had been occupied by the Union Navy earlier in the war. The whites had fled to the mainland while the blacks stayed. An early program of Reconstruction was set up for the former slaves, including schools and training. Naval officers read the proclamation and told them they were free.[87]

Slaves had been part of the "engine of war" for the Confederacy. They produced and prepared food; sewed uniforms; repaired railways; worked on farms and in factories, shipping yards, and mines; built fortifications; and served as hospital workers and common laborers. News of the Proclamation spread rapidly by word of mouth, arousing hopes of freedom, creating general confusion, and encouraging thousands to escape to Union lines.[101][page needed] George Washington Albright, a teenage slave in Mississippi, recalled that like many of his fellow slaves, his father escaped to join Union forces. According to Albright, plantation owners tried to keep news of the Proclamation from slaves, but they learned of it through the grapevine. The young slave became a "runner" for an informal group they called the 4Ls ("Lincoln's Legal Loyal League") bringing news of the proclamation to secret slave meetings at plantations throughout the region.[102]

Confederate general Robert E. Lee saw the Emancipation Proclamation as a way for the Union to increase the number of soldiers it could place on the field, making it imperative for the Confederacy to increase its own numbers. Writing on the matter after the sack of Fredericksburg, Lee wrote, "In view of the vast increase of the forces of the enemy, of the savage and brutal policy he has proclaimed, which leaves us no alternative but success or degradation worse than death, if we would save the honor of our families from pollution [and] our social system from destruction, let every effort be made, every means be employed, to fill and maintain the ranks of our armies, until God in his mercy shall bless us with the establishment of our independence."[103][104][page needed]

The Emancipation Proclamation marked a significant turning point in the war as it made the goal of the North not only preserving the Union, but also freeing the slaves.[105] The Proclamation also rallied support from abolitionists and Europeans, while encouraging enslaved individuals to escape to the North. This weakened the South's labor force while bolstering the North's ranks.[106]

Political impact

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2020) |

The Proclamation was immediately denounced by Copperhead Democrats, who opposed the war and advocated restoring the union by allowing slavery. Horatio Seymour, while running for governor of New York, cast the Emancipation Proclamation as a call for slaves to commit extreme acts of violence on all white southerners, saying it was "a proposal for the butchery of women and children, for scenes of lust and rapine, and of arson and murder, which would invoke the interference of civilized Europe".[112] The Copperheads also saw the Proclamation as an unconstitutional abuse of presidential power. Editor Henry A. Reeves wrote in Greenport's Republican Watchman that "In the name of freedom for Negroes, [the proclamation] imperils the liberty of white men; to test an utopian theory of equality of races which Nature, History and Experience alike condemn as monstrous, it overturns the Constitution and Civil Laws and sets up Military Usurpation in their stead."[112]

Racism remained pervasive on both sides of the conflict and many in the North supported the war only as an effort to force the South to stay in the Union. The promises of many Republican politicians that the war was to restore the Union and not about black rights or ending slavery were declared lies by their opponents, who cited the Proclamation. In Columbiana, Ohio, Copperhead David Allen told a crowd, "Now fellow Democrats I ask you if you are going to be forced into a war against your Britheren of the Southern States for the Negro. I answer No!"[113] The Copperheads saw the Proclamation as irrefutable proof of their position and the beginning of a political rise for their members; in Connecticut, H. B. Whiting wrote that the truth was now plain even to "those stupid thickheaded persons who persisted in thinking that the President was a conservative man and that the war was for the restoration of the Union under the Constitution."[113]

War Democrats, who rejected the Copperhead position within their party, found themselves in a quandary. While throughout the war they had continued to espouse the racist positions of their party and their disdain of the concerns of slaves, they did see the Proclamation as a viable military tool against the South and worried that opposing it might demoralize troops in the Union army. The question would continue to trouble them and eventually lead to a split within their party as the war progressed.[113]

Lincoln further alienated many in the Union two days after issuing the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation by suspending habeas corpus. His opponents linked these two actions in their claims that he was becoming a despot. In light of this and a lack of military success for the Union armies, many War Democrat voters who had previously supported Lincoln turned against him and joined the Copperheads in the off-year elections held in October and November.[113]

In the 1862 elections, the Democrats gained 28 seats in the House as well as the governorship of New York. Lincoln's friend Orville Hickman Browning told the president that the Proclamation and the suspension of habeas corpus had been "disastrous" for his party by handing the Democrats so many weapons. Lincoln made no response. Copperhead William Jarvis of Connecticut pronounced the election the "beginning of the end of the utter downfall of Abolitionism".[114]

Historians James M. McPherson and Allan Nevins state that though the results looked very troubling, they could be seen favorably by Lincoln; his opponents did well only in their historic strongholds and "at the national level their gains in the House were the smallest of any minority party's in an off-year election in nearly a generation. Michigan, California, and Iowa all went Republican.... Moreover, the Republicans picked up five seats in the Senate."[114] McPherson states, "If the election was in any sense a referendum on emancipation and on Lincoln's conduct of the war, a majority of Northern voters endorsed these policies."[114]

Confederate response

The initial Confederate response was outrage. The Proclamation was seen as vindication of the rebellion and proof that Lincoln would have abolished slavery even if the states had remained in the Union.[115] It intensified the fear of slaves revolting and undermined morale, especially spurring fear among slave owners who saw it as a threat to their business.[116] In an August 1863 letter to President Lincoln, U.S. Army general Ulysses S. Grant observed that the proclamation's "arming the negro", together with "the emancipation of the negro, is the heavyest [sic] blow yet given the Confederacy. The South rave a greatdeel [sic] about it and profess to be very angry."[117] In May 1863, a few months after the Proclamation took effect, the Confederacy passed a law demanding "full and ample retaliation" against the U.S. for such measures. The Confederacy stated that black U.S. soldiers captured while fighting against the Confederacy would be tried as slave insurrectionists in civil courts—a capital offense with an automatic sentence of death. Less than a year after the law's passage, the Confederates massacred black U.S. soldiers at Fort Pillow.[118][page needed]

Confederate President Jefferson Davis reacted to the Emancipation Proclamation with outrage and in an address to the Confederate Congress on January 12 threatened to send any U.S. military officer captured in Confederate territory covered by the proclamation to state authorities to be charged with "exciting servile insurrection", which was a capital offense.[119]

Confederate General Robert E. Lee called the Proclamation a "savage and brutal policy he has proclaimed, which leaves us no alternative but success or degradation worse than death."[120]

However, some Confederates welcomed the Proclamation, because they believed it would strengthen pro-slavery sentiment in the Confederacy and thus lead to greater enlistment of white men into the Confederate army. According to one Confederate cavalry sergeant from Kentucky, "The Proclamation is worth three hundred thousand soldiers to our Government at least.... It shows exactly what this war was brought about for and the intention of its damnable authors."[121] Even some Union soldiers concurred with this view and expressed reservations about the Proclamation, not on principle, but rather because they were afraid it would increase the Confederacy's determination to fight on and maintain slavery. One Union soldier from New York stated worryingly after the Proclamation's issuance, "I know enough of the southern spirit that I think they will fight for the institution of slavery even to extermination."[122]

As a result of the Proclamation, the price of slaves in the Confederacy increased in the months after its issuance, with one Confederate from South Carolina opining in 1865 that "now is the time for Uncle to buy some negro women and children...."[123]

International impact

As Lincoln had hoped, the proclamation turned foreign popular opinion in favor of the Union by gaining the support of anti-slavery countries and countries that had already abolished slavery (especially the developed countries in Europe such as the United Kingdom and France). This shift ended the Confederacy's hopes of gaining official recognition.[124]

Since the Emancipation Proclamation made the eradication of slavery an explicit Union war goal, it linked support for the South to support for slavery. Public opinion in Britain would not tolerate support for slavery. As Henry Adams noted, "The Emancipation Proclamation has done more for us than all our former victories and all our diplomacy." In Italy, Giuseppe Garibaldi hailed Lincoln as "the heir of the aspirations of John Brown". On August 6, 1863, Garibaldi wrote to Lincoln: "Posterity will call you the great emancipator, a more enviable title than any crown could be, and greater than any merely mundane treasure".[125]

Mayor Abel Haywood, a representative for workers from Manchester, England, wrote to Lincoln saying, "We joyfully honor you for many decisive steps toward practically exemplifying your belief in the words of your great founders: 'All men are created free and equal.'"[126] The Emancipation Proclamation served to ease tensions with Europe over the North's conduct of the war, and combined with the recent failed Southern offensive at Antietam, to remove any practical chance for the Confederacy to receive foreign military intervention in the war.[127]

However, in spite of the Emancipation Proclamation, arms sales to the Confederacy through blockade running, from British firms and dealers, continued, with knowledge of the British government.[128] The Confederacy was able to sustain the fight for two more years largely thanks to the weapons supplied by British blockade runners. As a result, the blockade runners operating from Britain were responsible for killing 400,000 additional soldiers and civilians on both sides.[129][130][131][132]

Gettysburg Address

Lincoln's Gettysburg Address on November 19, 1863 made indirect reference to the Proclamation and the ending of slavery as a war goal with the phrase "new birth of freedom". The Proclamation solidified Lincoln's support among the rapidly growing abolitionist elements of the Republican Party and ensured that they would not block his renomination in 1864.[133][page needed]

Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction (1863)

In December 1863, Lincoln issued his Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction, which dealt with the ways the rebel states could reconcile with the Union. Key provisions required that the states accept the Emancipation Proclamation and thus the freedom of their slaves, and accept the Confiscation Acts, as well as the Act banning slavery in United States territories.[134]

Postbellum

Near the end of the war, abolitionists were concerned that the Emancipation Proclamation would be construed solely as a war measure, as Lincoln intended, and would no longer apply once fighting ended. They also were increasingly anxious to secure the freedom of all slaves, not just those freed by the Emancipation Proclamation. Thus pressed, Lincoln staked a large part of his 1864 presidential campaign on a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery throughout the United States. Lincoln's campaign was bolstered by votes in both Maryland and Missouri to abolish slavery in those states. Maryland's new constitution abolishing slavery took effect on November 1, 1864.[135] Slavery in Missouri ended on January 11, 1865, when a state convention approved an ordinance abolishing slavery by a vote of 60-4,[136] and later the same day, Governor Thomas C. Fletcher followed up with his own "Proclamation of Freedom."[137]

Winning re-election, Lincoln pressed the lame duck 38th Congress to pass the proposed amendment immediately rather than wait for the incoming 39th Congress to convene. In January 1865, Congress sent to the state legislatures for ratification what became the Thirteenth Amendment, banning slavery in all U.S. states and territories, except as punishment for a crime. The amendment was ratified by the legislatures of enough states by December 6, 1865, and proclaimed 12 days later. There were approximately 40,000 slaves in Kentucky and 1,000 in Delaware who were liberated then.[138]

Critiques

Lincoln's proclamation has been called "one of the most radical emancipations in the history of the modern world."[139] Nonetheless, as over the years American society continued to be deeply unfair towards black people, cynicism towards Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation increased. One attack was Lerone Bennett's Forced into Glory: Abraham Lincoln's White Dream (2000), which claimed that Lincoln was a white supremacist who issued the Emancipation Proclamation in lieu of the real racial reforms for which radical abolitionists pushed. To this, one scholarly review states that "Few Civil War scholars take Bennett and DiLorenzo seriously, pointing to their narrow political agenda and faulty research."[140] In his Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, Allen C. Guelzo noted professional historians' lack of substantial respect for the document, since it has been the subject of few major scholarly studies. He argued that Lincoln was the U.S.'s "last Enlightenment politician"[141] and as such had "allegiance to 'reason, cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason'.... But the most important among the Enlightenment's political virtues for Lincoln, and for his Proclamation, was prudence".[142]

Other historians have given more credit to Lincoln for what he accomplished toward ending slavery and for his own growth in political and moral stature.[143] More might have been accomplished if he had not been assassinated. As Eric Foner wrote:

Lincoln was not an abolitionist or Radical Republican, a point Bennett reiterates innumerable times. He did not favor immediate abolition before the war, and held racist views typical of his time. But he was also a man of deep convictions when it came to slavery, and during the Civil War displayed a remarkable capacity for moral and political growth.[144]

Kal Ashraf wrote:

Perhaps in rejecting the critical dualism—Lincoln as individual emancipator pitted against collective self-emancipators—there is an opportunity to recognise the greater persuasiveness of the combination. In a sense, yes: a racist, flawed Lincoln did something heroic, and not in lieu of collective participation, but next to, and enabled, by it. To venerate a singular 'Great Emancipator' may be as reductive as dismissing the significance of Lincoln's actions. Who he was as a man, no one of us can ever really know. So it is that the version of Lincoln we keep is also the version we make.[145]

Legacy in the civil rights era

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. made many references to the Emancipation Proclamation during the civil rights movement. These include an "Emancipation Proclamation Centennial Address" he gave in New York City on September 12, 1962, in which he placed the Proclamation alongside the Declaration of Independence as an "imperishable" contribution to civilization and added, "All tyrants, past, present and future, are powerless to bury the truths in these declarations...." He lamented that despite a history where the United States "proudly professed the basic principles inherent in both documents," it "sadly practiced the antithesis of these principles." He concluded, "There is but one way to commemorate the Emancipation Proclamation. That is to make its declarations of freedom real; to reach back to the origins of our nation when our message of equality electrified an unfree world, and reaffirm democracy by deeds as bold and daring as the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation."[146]

King's most famous invocation of the Emancipation Proclamation was in a speech from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial at the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (often referred to as the "I Have a Dream" speech). King began the speech saying "Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity. But one hundred years later, we must face the tragic fact that the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination."[147]

The "Second Emancipation Proclamation"

In the early 1960s, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his associates called on President John F. Kennedy to bypass Southern segregationist opposition in the Congress by issuing an executive order to put an end to segregation.[148] This envisioned document was referred to as the "Second Emancipation Proclamation". Kennedy, however, did not issue a second Emancipation Proclamation "and noticeably avoided all centennial celebrations of emancipation." Historian David W. Blight points out that, although the idea of an executive order to act as a second Emancipation Proclamation "has been virtually forgotten," the manifesto that King and his associates produced calling for an executive order showed his "close reading of American politics" and recalled how moral leadership could have an effect on the American public through an executive order. Despite its failure "to spur a second Emancipation Proclamation from the White House, it was an important and emphatic attempt to combat the structured forgetting of emancipation latent within Civil War memory."[149]

President John F. Kennedy

On June 11, 1963, President Kennedy spoke on national television about civil rights. Kennedy, who had been routinely criticized as timid by some civil rights activists, reminded Americans that two black students had been peacefully enrolled in the University of Alabama with the aid of the National Guard, despite the opposition of Governor George Wallace.

John Kennedy called it a "moral issue."[150] Invoking the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation he said,

One hundred years of delay have passed since President Lincoln freed the slaves, yet their heirs, their grandsons, are not fully free. They are not yet freed from the bonds of injustice. They are not yet freed from social and economic oppression. And this Nation, for all its hopes and all its boasts, will not be fully free until all its citizens are free. We preach freedom around the world, and we mean it, and we cherish our freedom here at home, but are we to say to the world, and much more importantly, to each other that this is a land of the free except for the Negroes; that we have no second-class citizens except Negroes; that we have no class or caste system, no ghettoes, no master race except with respect to Negroes? Now the time has come for this Nation to fulfill its promise. The events in Birmingham and elsewhere have so increased the cries for equality that no city or State or legislative body can prudently choose to ignore them.[151]

In the same speech, Kennedy announced he would introduce a comprehensive civil rights bill in the United States Congress, which he did a week later. Kennedy pushed for its passage until he was assassinated on November 22, 1963. Historian Peniel E. Joseph holds Lyndon Johnson's ability to get that bill, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, signed into law on July 2, 1964, to have been aided by "the moral forcefulness of the June 11 speech", which had turned "the narrative of civil rights from a regional issue into a national story promoting racial equality and democratic renewal."[150]

President Lyndon B. Johnson

During the civil rights movement of the 1960s, Lyndon B. Johnson invoked the Emancipation Proclamation, holding it up as a promise yet to be fully implemented.

As vice president, while speaking from Gettysburg on May 30, 1963 (Memorial Day), during the centennial year of the Emancipation Proclamation, Johnson connected it directly with the ongoing civil rights struggles of the time, saying "One hundred years ago, the slave was freed. One hundred years later, the Negro remains in bondage to the color of his skin.... In this hour, it is not our respective races which are at stake—it is our nation. Let those who care for their country come forward, North and South, white and Negro, to lead the way through this moment of challenge and decision.... Until justice is blind to color, until education is unaware of race, until opportunity is unconcerned with color of men's skins, emancipation will be a proclamation but not a fact. To the extent that the proclamation of emancipation is not fulfilled in fact, to that extent we shall have fallen short of assuring freedom to the free."[152]

As president, Johnson again invoked the proclamation in a speech presenting the Voting Rights Act at a joint session of Congress on Monday, March 15, 1965. This was one week after violence had been inflicted on peaceful civil rights marchers during the Selma to Montgomery marches. Johnson said "it's not just Negroes, but really it's all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome. As a man whose roots go deeply into Southern soil, I know how agonizing racial feelings are. I know how difficult it is to reshape the attitudes and the structure of our society. But a century has passed—more than 100 years—since the Negro was freed. And he is not fully free tonight. It was more than 100 years ago that Abraham Lincoln—a great President of another party—signed the Emancipation Proclamation. But emancipation is a proclamation and not a fact. A century has passed—more than 100 years—since equality was promised, and yet the Negro is not equal. A century has passed since the day of promise, and the promise is unkept. The time of justice has now come, and I tell you that I believe sincerely that no force can hold it back. It is right in the eyes of man and God that it should come, and when it does, I think that day will brighten the lives of every American."[153]

In popular culture

In the 1963 episode of The Andy Griffith Show, "Andy Discovers America", Andy asks Barney to explain the Emancipation Proclamation to Opie who is struggling with history at school.[155] Barney brags about his history expertise, yet it is apparent he cannot answer Andy's question. He finally becomes frustrated and explains it is a proclamation for certain people who wanted emancipation.[156] In addition, the Emancipation Proclamation was also a main item of discussion in the movie Lincoln (2012) directed by Steven Spielberg.[157]

The Emancipation Proclamation is celebrated around the world, including on stamps of nations such as the Republic of Togo.[158] The United States commemorative was issued on August 16, 1963, the opening day of the Century of Negro Progress Exposition in Chicago, Illinois. Designed by Georg Olden, an initial printing of 120 million stamps was authorized.[154]

See also

- History of slavery in Alabama

- History of slavery in Arkansas

- District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act

- History of slavery in Florida

- History of slavery in Georgia

- History of slavery in Kentucky

- History of slavery in Louisiana

- History of slavery in Maryland

- History of slavery in Missouri

- History of slavery in Mississippi

- History of slavery in North Carolina

- History of slavery in South Carolina

- History of slavery in Tennessee

- History of slavery in Texas

- Juneteenth emancipation in Texas

- History of slavery in Virginia

- Abolition of slavery timeline

- Act Prohibiting the Return of Slaves – 1862 statute

- Confiscation Acts

- Contraband (American Civil War)

- Emancipation Memorial – a sculpture in Washington, D.C., completed in 1876

- Emancipation reform of 1861 – Russia

- Lieber Code

- Reconstruction Amendments – amendments added to the Constitution after 1863

- Slavery Abolition Act 1833 – an act passed by the British parliament abolishing slavery in British colonies with compensation to the owners

- Slave Trade Acts

- Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution – 1865, abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime.

- Timeline of the civil rights movement

- War Governors' Conference – gave Lincoln the much needed political support to issue the Proclamation

Notes

- ^ "Featured Document: The Emancipation Proclamation". n.d.

- ^ Archived from the original on December 18, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ Harward, Brian (2020). Archived from the original on April 23, 2022. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ Text of Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation

- ^ Text of Emancipation Proclamation

- ^ Eleven states had seceded, but Tennessee was under Union control.

- ^ Dirck, Brian R. (2007). 102. ISBN 978-1851097913.

The Emancipation Proclamation was an executive order, itself a rather unusual thing in those days. Executive orders are simply presidential directives issued to agents of the executive department by its boss.

- ^ a b Davis, Kenneth C. (2003). Don't Know Much About History: Everything You Need to Know About American History but Never Learned (1st ed.). New York: HarperCollins. pp. 227–228. ISBN 978-0-06-008381-6.

- ^ Allan Nevins, Ordeal of the Union, vol. 6: War Becomes Revolution, 1862–1863 (1960) pp. 231–241, 273

- ^ Jones, Howard (1999). Abraham Lincoln and a New Birth of Freedom: The Union and Slavery in the Diplomacy of the Civil War. University of Nebraska Press. p. 151. ISBN 0-8032-2582-2.

- ^ the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ "13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution". The Library of Congress. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- ^ Jean Allain (2012). The Legal Understanding of Slavery: From the Historical to the Contemporary. Oxford University Press. p. 117. ISBN 9780199660469.

- ^ Foner 2010, p. 16

- ^ Jean Allain (2012). The Legal Understanding of Slavery: From the Historical to the Contemporary. Oxford University Press. pp. 119–120. ISBN 9780199660469.

- ^ Tsesis, The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom: A Legal History (2004), p. 14. "Nineteenth century apologists for the expansion of slavery developed a political philosophy that placed property at the pinnacle of personal interests and regarded its protection to be the government's chief purpose. The Fifth Amendment's Just Compensation Clause provided the proslavery camp with a bastion for fortifying the peculiar institution against congressional restrictions to its spread westward. Based on this property-rights-centered argument, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, in his infamous Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) decision, found the Missouri Compromise unconstitutionally violated substantive due process".

- ^ Tsesis, The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom (2004), pp. 18–23. "Constitutional protections of slavery coexisted with an entire culture of oppression. The peculiar institution reached many private aspects of human life, for both whites and blacks.... Even free Southern blacks lived in a world so legally constricted by racial domination that it offered only a deceptive shadow of freedom."

- ^ Foner 2010, pp. 14–16

- ^ Mackubin, Thomas Owens (March 25, 2004). the original on February 16, 2012.

- ^ Crowther, p. 651

- ^ Fabrikant, Robert, "Emancipation and the Proclamation: Of Contrabands, Congress, and Lincoln". Howard Law Journal, vol. 49, no. 2 (2006), p. 369.

- ^ "The Emancipation Proclamation" (transcription). United States National Archives. January 1, 1863.

- ^ The fourth paragraph of the proclamation explains that Lincoln issued it "by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief, of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion".[22]

- ^ "150 years later, myths persist about the Emancipation Proclamation". CNN. January 1, 2013. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ Irwin, Richard Bache; Banks, Nathaniel Prentiss (January 29, 1863).

- ^ Freedmen and Southern Society Project (1982). 69. ISBN 978-0-521-22979-1.

- ^ Foner 2010, pp. 241–242

- ^ Hofstadter, Richard, "Abraham Lincoln and the Self-Made Myth," in The American Political Tradition and the Men Who Made It (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1948). online. Vintage Books edition, March 1989, p. 169.

- ^ Allen C. Guelzo quotes Karl Marx's statement that the proclamation sounds like "ordinary summonses sent by one lawyer to another on the opposing side".

- ^ Freehling, William W., The South vs. The South: How Anti-Confederate Southerners Shaped the Course of the Civil War. Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 118.

- ^ the original on February 20, 2012. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ^ the original on April 25, 2012.

- ^ "Tennessee State Convention: Slavery Declared Forever Abolished". The New York Times. January 14, 1865.

- ^ "On This Day in West Virginia History – February". www.wvculture.org.

- ^ Stauffer (2008), Giants, p. 279

- ^ Peterson (1995), Lincoln in American Memory, pp. 38–41

- ^ McCarthy (1901), Lincoln's plan of Reconstruction, p. 76

- ^ Harrison, Lowell H. (1983). "Slavery in Kentucky: A Civil War Casualty". The Kentucky Review. 5 (1) (Fall ed.): 38–40.

- ^ "Slavery in Delaware". slavenorth.com.

- ^ Lowell Hayes Harrison and James C. Klotter (1997). A new history of Kentucky. University Press of Kentucky. p. 180. ISBN 0813126215. In 1866, Kentucky refused to ratify the 13th Amendment. It did ratify it in 1976.

- ^ Adam Goodheart (April 1, 2011). the original on January 1, 2022. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- ^ Oakes, James, Freedom National, p. 99.

- ^ "Living Contraband – Former Slaves in the Nation's Capital During the Civil War". Civil War Defenses of Washington. National Park Service. Retrieved June 29, 2013.

- ^ December 3, 1861: First Annual Message: Transcript

- ^ Striner, Richard (2006). 147–148. ISBN 978-0-19-518306-1.

- ^ "Law Enacting an Additional Article of War" (the official name of the statute).

- ^ Mann, Lina. "The Complexities of Slavery in the Nation's Capital". White House Historical. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Guminski, Arnold. The Constitutional Rights, Privileges, and Immunities of the American People, page 241 (2009).

- ^ Richardson, Theresa and Johanningmeir, Erwin. Race, ethnicity, and education, page 129 (IAP 2003).

- ^ Montgomery, David. The Student's American History, p. 428 (Ginn & Co. 1897).

- ^ Keifer, Joseph. Slavery and Four Years of War, p. 109 (Echo Library 2009).

- ^ First Confiscation Act

- ^ the original on August 6, 2008. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- ^ "The Second Confiscation Act, July 17, 1862". www.freedmen.umd.edu.

- ^ Donald, David. Lincoln, p. 365 (Simon and Schuster, 1996)

- ^ a b Holzer, Harold (2006). Dear Mr. Lincoln: Letters to the President (2nd ed.). Southern Illinois University Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-8093-2686-0.

- ^ Holzer, Harold (2006). Dear Mr. Lincoln: Letters to the President (second ed.). Southern Illinois University Press. pp. 160–161. ISBN 978-0-8093-2686-0.

- ^ Basler, Roy P., ed. (1953). 389. ISBN 9781434477071.

- ^ a b Striner, Richard (2006). 176. ISBN 978-0-19-518306-1.

- ^ Freehling, William W. (2001). The South vs. The South: How Anti-Confederate Southerners Shaped the Course of the Civil War, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 111.

- ^ Cohen, Henry, "Was Lincoln Disingenuous in His Greeley Letter?", The Lincoln Forum Bulletin, Issue 54, Fall 2023, pp. 8-9.

- ^ Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. 5, pp. 462-463, 470, 500.

- ^ Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. 5, p. 530.

- ^ Brewster, Todd (2014). Lincoln's Gamble: The Tumultuous Six Months that Gave America the Emancipation Proclamation and Changed the Course of the Civil War. Scribner. p. 59. ISBN 978-1451693867.

- ^ Brewster, Todd (2014). Lincoln's Gamble: The Tumultuous Six Months that Gave America the Emancipation Proclamation and Changed the Course of the Civil War. Scribner. p. 236. ISBN 978-1451693867.

- ^ Guelzo 2006, p. 18

- ^ Kolchin, Peter (1994). American Slavery: 1619–1877. New York: Hill and Wang. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-8090-1554-2.

- ^ "Emancipation Proclamation". Lincoln Papers. Library of Congress and Knox College. 2002. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ Goodwin, Doris Kearns (2005). Team of Rivals. New York: Blithedale Productions.

- ^ Stahr, Walter, Stanton: Lincoln's War Secretary, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017, p. 226.

- ^ "Preliminary Emacipation Proclamation, 1862". www.archives.gov.

- ^ McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom, (1988), p. 557.

- ^ Carpenter, Frank B. (1866). Six Months at the White House. Applewood Books. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-4290-1527-1. Retrieved February 20, 2010. as reported by Secretary of the Treasury, Salmon Portland Chase, September 22, 1862. Others present used the word resolution instead of vow to God.

Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy Under Lincoln and Johnson (Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1911), 1:143, reported that Lincoln made a covenant with God that if God would change the tide of the war, Lincoln would change his policy toward slavery. See also Nicolas Parrillo, "Lincoln's Calvinist Transformation: Emancipation and War", Civil War History (September 1, 2000). - ^ "Bangor in Focus: Hannibal Hamlin". Bangorinfo.com. n.d. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- ^ "The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln" edited by Roy P. Basler, Volume 6, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Cohen, Henry, "Was Lincoln Disingenuous in His Greeley Letter?", The Lincoln Forum Bulletin, Issue 54, Fall 2023, p. 9.

- ^ Oakes, James, Freedom National, p. 367.

- ^ "Teaching With Documents: The Fight for Equal Rights: Black Soldiers in the Civil War". U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. August 15, 2016.

- ^ the original on March 12, 2012. Retrieved April 13, 2012.

- ^ "Constitutional Convention, Virginia (1864)". encyclopediavirginia.org. Retrieved October 11, 2016.

- ^ "American Civil War April 1864 – History Learning Site". History Learning Site. Retrieved October 11, 2016.

- ^ the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- ^ "TSLA: This Honorable Body: African American Legislators in 19th Century Tennessee". State.tn.us. n.d. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- ^ "Transcript of the Proclamation". National Archives. October 6, 2015. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Richard Duncan, Beleaguered Winchester: A Virginia Community at War (Baton Rouge, LA: LSU Press, 2007), pp. 139–40

- ^ Ira Berlin et al., eds., Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation 1861–1867, Vol. 1: The Destruction of Slavery (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1985), p. 260

- ^ a b William Klingaman, Abraham Lincoln and the Road to Emancipation, 1861–1865 (NY: Viking Press, 2001), p. 234

- ^ "Important From Key West", The New York Times February 4, 1863, p. 1

- ^ a b From Our Own Correspondent (January 9, 1863). "Interesting from Port Royal". The New York Times. p. 2.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Samuel Wilkeson Jr". Buffalo Courier Express. December 8, 1889. p. 1. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ "The Historical Legacy of Juneteenth". National Museum of African American History and Culture. June 19, 2019. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- ^ James M. Paradis (2012). African Americans and the Gettysburg Campaign. Scarecrow Press. p. 90. ISBN 9780810883369.

- ^ Kenneth L. Deutsch; Joseph Fornieri (2005). Lincoln's American Dream: Clashing Political Perspectives. Potomac Books. p. 35. ISBN 9781597973908.

- ^ "News from South Carolina: Negro Jubilee at Hilton Head", New York Herald, January 7, 1863, p. 5

- ^ a b Poulter, Keith, "Slaves Immediately Freed by the Emancipation Proclamation", North & South, vol. 5, no. 1 (December 2001), p. 48.

- ^ Epps, Henry, A Concise Chronicle History of African-American People Experience in America, SCL, 2012, p. 109

- ^ Harris, "After the Emancipation Proclamation", p. 45

- ^ Allen C. Guelzo (2006). Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America. Simon & Schuster. pp. 107–8. ISBN 9781416547952.

- ^ Gallagher, Gary W., The Union War, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2011, pp. 142-143.

- ^ Booker T. Washington (1907). 19-21.

- ^ Goodheart, Adam (2011). 1861: The Civil War Awakening. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

- ^ Jenkins, Sally, and Stauffer, John. The State of Jones. New York: Anchor Books, 2010. ISBN 978-0-7679-2946-2, p. 42.

- ^ "Robert E. Lee on Robert H. Milroy or Emancipation," civil war memory: The Online Home of Kevin M. Levin, November 18, 2011

- ^ Shelby Foote (1963). The Civil War: A Narrative: Fredericksburg to Meridian. Vol. 2. Random House.

- ^ "Emancipation Proclamation (1863)". National Archives. May 10, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ "Immediate Effects of the Emancipation Proclamation". Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ Punch, Volume 43, October 18, 1862, p. 161

- ^ "London Times Editorial". October 6, 1862. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ^ "International Reaction".

- ^ "Abe Lincoln's Last Card". October 18, 1862.

- ^ Mitgang, Herbert (2000). Abraham Lincoln, a Press Portrait: His Life and Times from the Original Newspaper Documents of the Union, the Confederacy, and Europe. Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-8232-2062-5.

- ^ a b Weber, Jennifer L. (2006). Copperheads: The Rise and Fall of Lincoln's Opponents in the North. New York City: Oxford University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-19-530668-2.

- ^ a b c d Weber, Jennifer L. (2006). Copperheads: The Rise and Fall of Lincoln's Opponents in the North. New York City: Oxford University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-19-530668-2.

- ^ a b c Weber, Jennifer L. (2006). Copperheads: The Rise and Fall of Lincoln's Opponents in the North. New York City: Oxford University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-19-530668-2.

- ^ "The Rebel Message: What Jefferson Davis Has to Say". New York Herald. America's Historical Newspapers. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ "The Emancipation Proclamation: Striking a Mighty Blow to Slavery". National Museum of African History and Culture – Smithsonian. Smithsonian. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ Grant, Ulysses (August 23, 1863). the original on May 3, 2014. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

I have given the subject of arming the Negro my hearty support. This, with the emancipation of the Negro, is the heaviest blow yet given the Confederacy. The South rave a greatdeel about it and profess to be very angry.

- ^ Tap, Bruce (2013). The Fort Pillow Massacre: North, South, and the Status of African Americans in the Civil War Era. Routledge.

- ^ the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ Lee Family Digital Archive

- ^ McPherson, James M. (1997). 34912692. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ^ McPherson, James M. (1997). 34912692. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ^ McPherson, James M. (1997). 34912692. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ^ Robert E. May (1995). "History and Mythology: The Crisis over British Intervention in the Civil War". 29–68. ISBN 978-1-55753-061-5.

- ^ Mack Smith, p. 72

- ^ Quoted in James Lander (2010). Lincoln and Darwin: Shared Visions of Race, Science, and Religion. Southern Illinois University Press. p. 221. ISBN 9780809329908.

- ^ Kevin Phillips (2000). The Cousins' Wars: Religion, Politics, Civil Warfare, And The Triumph Of Anglo-America. Basic Books. p. 493. ISBN 9780465013708.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Edward Hawkins Sisson (June 22, 2014). America the Great. Edward Sisson. p. 1169.

- ^ David Keys (June 24, 2014). "Historians reveal secrets of UK gun-running which lengthened the American civil war by two years". The Independent.

- ^ Paul Hendren (April 1933). "The Confederate Blockade Runners". United States Naval Institute.

- ^ Peter G. Tsouras (March 11, 2011). "American Civil War viewpoints: It was British arms that sustained the Confederacy". Military History Matters.

- ^ Beau Cleland. Between King Cotton and Queen Victoria: Confederate Informal Diplomacy and Privatized Violence in British America During the American Civil War (Thesis). University of Calgary. p. 2.

British resources were, in fact, essential to the rebellion's survival. In the face of a blockade that after 1861 made direct imports nearly impossible, the overwhelming majority of the arms and supplies that the Confederacy received from abroad passed through British colonies en route from Europe, usually on British-flagged ships, consigned to British merchants, and paid for with cotton that followed the same path out of Southern ports. Without the advantage provided by British (and to a far lesser extent, Spanish) colonies, the Confederacy had no prayer of military victory. The colonies were unsinkable, unassailable refuges in an enemy-controlled sea.

- ^ Allan Nevins, Ordeal of the Union: vol. 6. War Becomes Revolution, 1862–1863 (1960).

- ^ Richter, William L. (2009). The A to Z of the Civil War and Reconstruction. Scarecrow Press. pp. 479–480. ISBN 9780810863361.

- ^ White, Jonathan W., "Achieving Emancipation in Maryland," in The Civil War in Maryland Reconsidered, edited by Charles W. Mitchell and Jean H. Baker, Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2021, p. 249.

- ^ Missouri (1865). Journal of the Missouri state convention, held at the city of St. Louis January 6-April 10, 1865. St. Louis: Missouri Democrat. pp. 25–26. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ Fletcher, Thomas C. (1865). Missouri's Jubilee. Jefferson City, MO: W. A. Curry, Public Printer. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ "Census, Son of the South". sonofthesouth.net. 1860.

- ^ Hahn, Steven (January 13, 2011). 0028-6583.

- ^ Dirck, Brian (September 2009). 143986160.

- ^ Guelzo 2006, p. 3

- ^ Guelzo 2006, p. 3

- ^ Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005

- ^ Foner, Eric (April 9, 2000). Archived from the original on October 27, 2004. (book review)

- ^ Ashraf, Kal (March 2013). the original (PDF) on June 23, 2021. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ^ Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. "Dr. Martin Luther King on the Emancipation Proclamation". National Park Service.

- ^ Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (August 28, 1963). the original on July 23, 2014. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ^ Draft of Second Emancipation Proclamation

- ^ Blight, David W. and Allison Scharfstein, "King's Forgotten Manifesto". The New York Times, May 16, 2012.

- ^ a b Peniel E. Joseph (June 10, 2013). the original on January 1, 2022.

- ^ John F. Kennedy (June 11, 1963). "237 – Radio and Television Report to the American People on Civil Rights".

- ^ the original on March 29, 2012.

- ^ Lyndon B. Johnson (March 15, 1965). "We Shall Overcome".

- ^ a b "Emancipation Proclamation Issue", Arago: people, postage & the post, Smithsonian National Postal Museum, viewed September 28, 2014

- ^ the original on November 13, 2013.