Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

Going into Supreme Court arguments over President Donald Trump’s tariffs on Wednesday, it was genuinely difficult to guess how the justices would rule. Within minutes, that suspense vanished. The hearing was a bloodbath for the Trump administration: Six justices lined up to bash the Justice Department’s defense of the tariffs, barely disguising their annoyance with the government’s barrage of blustery nonsense. At the halfway point, it would’ve saved everyone time had the court just huddled, announced its decision from the bench, and recessed early for lunch. Trump’s signature trade policy—which he expected to raise trillions of dollars for him to use as he wished—looks dead on arrival at SCOTUS. We have spent 10 months waiting to see if, and when, this court would set a limit on Trump’s power. Perhaps we should’ve guessed that its extraordinary deference to this president could be outweighed only by its hatred of taxes.

Wednesday’s case, Learning Resources v. Trump, marks a direct challenge to Trump’s unprecedented, unilateral imposition of not a problem at all).

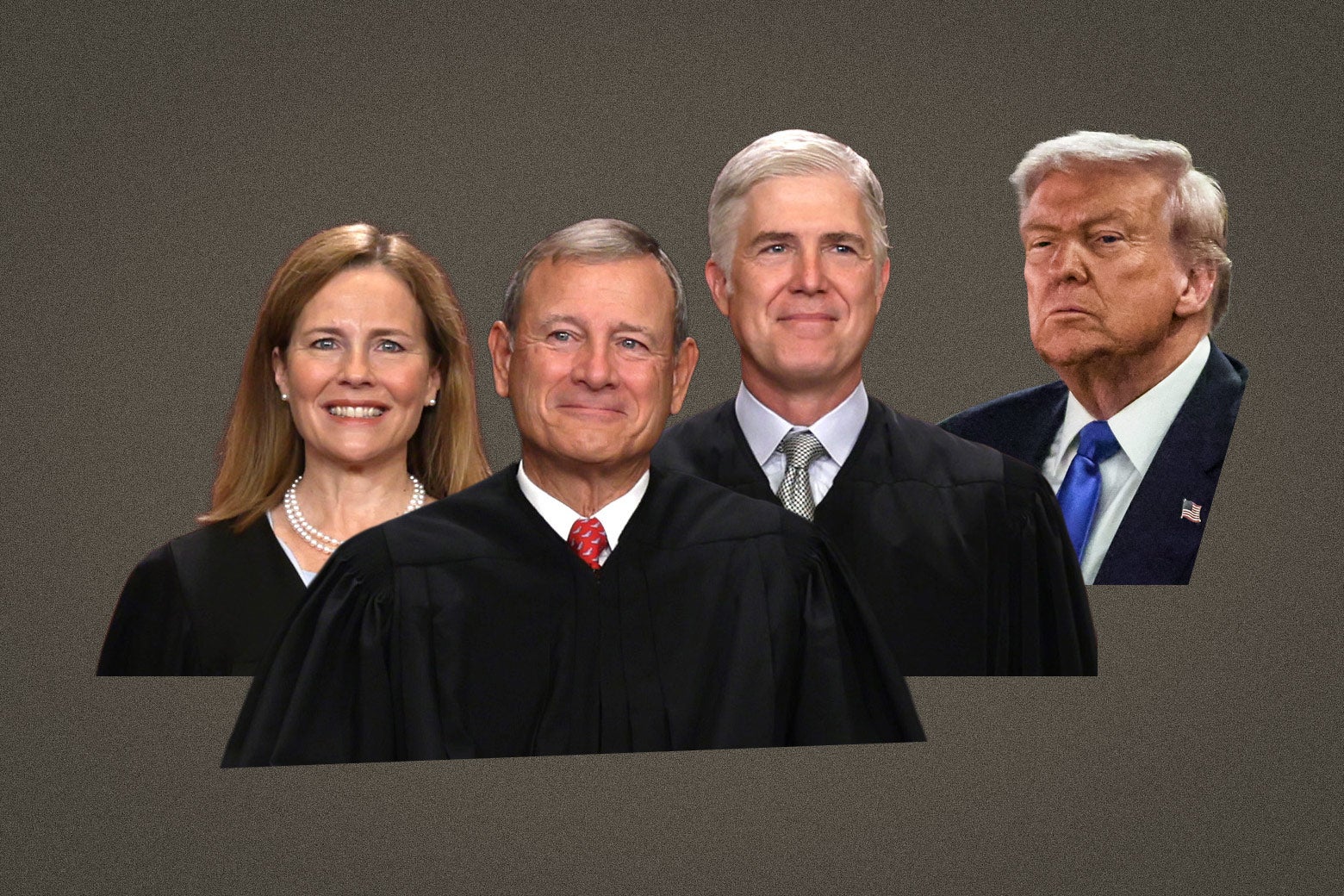

From the outset, a majority of justices weren’t buying what Sauer was selling. He stumbled early by irritating Chief Justice John Roberts with a heavy-handed invocation of Dames & Moore v. Regan, a 1981 decision about IEEPA. Roberts, who may have helped draft the opinion as a clerk, was plainly displeased by Sauer’s distortion of it. “That argument surprises me,” he told Sauer sternly, before reeling off passages from the ruling that undercut Trump’s position—including its warning that the case carries “little precedential value for subsequent cases.” With audible derision, Roberts concluded: “I don’t understand how you can get as much out of Dames & Moore as you’re trying to get.”

The solicitor general whiffed again with Roberts when he argued that the “major questions doctrine” does not apply to Trump’s tariffs. This doctrine bars the president from enacting an initiative of “vast economic or political significance” without explicit congressional authorization. Sauer insisted that it doesn’t apply here because tariffs implicate the president’s “foreign affairs” authority rather than domestic policy, giving him heightened constitutional discretion to do what he pleases. The chief was not convinced.

“It seems that it might be directly applicable,” he lectured Sauer. “You have a claimed source, IEEPA, that had never before been used to justify tariffs. No one has argued that it does till this particular case.” Yet now Trump claims it allows him to “impose tariffs on any product from any country in any amount for any length of time.” The “basis for the claim” of this “major authority,” Roberts concluded, “seems to be a misfit.”

Sauer shot back that tariffs are exempt from such scrutiny because they involve international relations, a core presidential power. But Roberts reminded him that, at bottom, tariffs are an “imposition of taxes on Americans,” something that “has always been the core power of Congress.” Sauer insisted that “foreign producers” shoulder the tariffs, but the chief wasn’t buying it. “Well, who pays the tax?” he asked. “If a tariff is imposed on automobiles, who pays them?”

Justice Neil Gorsuch zeroed in on Sauer’s attempt to quietly transfer Congress’ taxing authority to the executive branch. “You say we shouldn’t be concerned because this is foreign affairs and the president has inherent authority,” Gorsuch said. “If that’s true, what would prohibit Congress from just abdicating all responsibility to regulate foreign commerce—for that matter, declare war—to the president?” Could Congress decide that “we’re tired of this legislating business” and “hand it all off to the president?” Sauer backtracked a bit, acknowledging that Congress could not undertake an “abdication” of its duties; the justice wryly told him he was “delighted to hear that.”

Gorsuch followed up with a straightforward query: “Could the president impose a 50 percent tariff on gas-powered cars and autoparts to deal with the unusual and extraordinary threat from abroad of climate change?” Sauer admitted that he probably could, though he added that Trump would not because he rejects the “hoax” of climate change. “I think that has to be the logic of your view,” Gorsuch said sharply. He then asked: If Congress really did give the executive branch absolute freedom over tariffs, “what president is ever going to give that power back” by signing a bill that reins in IEEPA? Sauer hedged, but Gorsuch answered for him: “As a practical matter, in the real world,” Congress “can never get that power back.”

Justice Amy Coney Barrett sounded frustrated by the solicitor general’s hodgepodge of half-formed arguments, too, and cut through them with a poison dart of a question: “Can you point to any other place in the code, any other time in history, where that phrase together—‘regulate importation’—has been used to confer tariff-imposing authority?” All Sauer could point to was a predecessor to IEEPA that President Richard Nixon used to impose a 10 percent tariff in 1971. But, as Barrett pointed out, that dubious action was narrowed the president’s powers when it replaced the former statute with IEEPA, in direct response to Nixon’s actions. So, Barrett wondered, is there any other example? Sauer waffled, prompting Justice Sonia Sotomayor to leap in and tell him: “Could you just answer the justice’s question?” (It is never a good sign for your side when Sotomayor and Barrett are teaming up against you.) Finally, the solicitor general had to admit that he had no other examples.

Sotomayor, along with Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson, played backup nicely throughout the morning, pressing Sauer on the areas where their colleagues expressed the most skepticism. Kagan built off Barrett’s colloquy to ask whether there is any other place in federal law “where ‘regulate’ includes taxing power.” (The answer is no.) “The natural understanding of ‘regulate,’ ” the justice told him, doesn’t include “duties or taxes or tariffs or anything of the kind.” Sotomayor drilled down on the obviously pretextual nature of the stated “emergencies” at issue, leading Barrett to ask if “every country” truly “needed to be tariffed because of threats to the defense and industrial base.” How does slapping tariffs on Spain and France protect the nation’s security? All Sauer could cite was economically illiterate document was a substitute for reality-based reasoning.

But some of her colleagues may have been. Justice Brett Kavanaugh emerged as, at a minimum, tariff-curious early on, and grew increasingly active in his defense of Trump’s plan. He kept citing Nixon’s tariffs—a precedent that Barrett so deftly deconstructed—as evidence that Congress did intend to let the president tax imports all on his own. Justice Samuel Alito was characteristically dyspeptic with Neal Katyal, who represented the private plaintiffs, viciously and needlessly accusing him of betraying his personal principles to win this case for his clients. Justice Clarence Thomas’ questions didn’t quite cohere into a legible position, but he has staunchly supported Trump’s abuses of office, and may well be inclined to defend this one, too.

Still, it’s hard to see how this case comes out as anything less than a 6–3 loss for the administration. Roberts, Gorsuch, and Barrett’s questioning of Katyal was far friendlier than their grilling of Sauer, who spoke in a frothy jumble of run-on sentences that was often hard to understand. (Jackson even noted at one point that he was speaking too quickly.) It sounded as if this trio was trying to figure out how they’ll rule against Trump: Must they invoke the major questions doctrine, as Gorsuch suggested to Katyal? Or can they rest a decision on the plain text alone? For Roberts, the case might present an irresistible opportunity to get the liberals on board with his very recently invented doctrine, whose only use until now has been to box in President Joe Biden. If he assigns himself the opinion of the court, he can leave them with little choice but to hold their noses and sign onto it for the sake of forming a majority. That would be a real coup for the chief: pressuring the liberals into validating a theory that they’ve harshly rejected for years, and doing so in a way that lets him claim it as an evenhanded and legitimate tool, not simply one neat trick to reject all Democratic presidents’ policies.

More questions remain: What happens to the $200 billion in tariffs that the government has already collected? Will the court order it paid back, or only issue relief moving forward (or perhaps merely to the specific plaintiffs in this case, whom the government promised to reimburse should it lose)? Can the justices rush out an opinion before that figure balloons higher? Will Trump try to issue new tariffs under typically favor? Maybe. But who cares? What’s important is that, for the first time in a long time, they have finally found a line they won’t let Donald Trump cross.