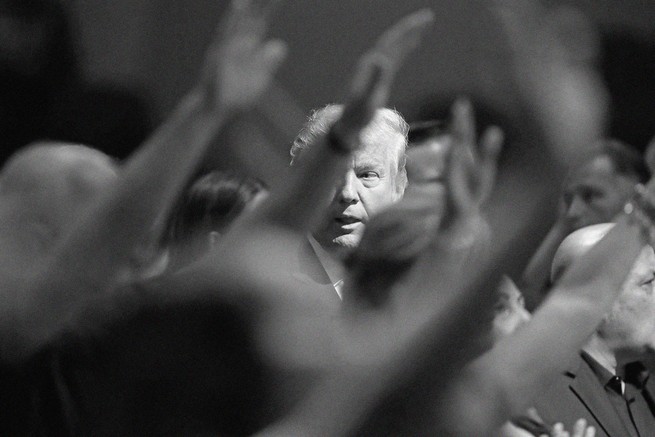

One of the most extraordinary things about our current politics—really, one of the most extraordinary developments of recent political history—is the loyal adherence of religious conservatives to Donald Trump. The president won get the Audm iPhone app.

Trump’s background and beliefs could hardly be more incompatible with traditional Christian models of life and leadership. Trump’s past political stances (he once supported the right to partial-birth abortion), his character (he has bragged about sexually assaulting women), and even his language (he introduced the words pussy and shithole into presidential discourse) would more naturally lead religious conservatives toward exorcism than alliance. This is a man who has cruelly publicized his infidelities, made disturbing sexual comments about his elder daughter, and boasted about the size of his penis on the debate stage. His lawyer reportedly arranged a $130,000 payment to a porn star to dissuade her from disclosing an alleged affair. Yet religious conservatives who once blanched at PG-13 public standards now yawn at such NC-17 maneuvers. We are a long way from The Book of Virtues.

Trump supporters tend to dismiss moral scruples about his behavior as squeamishness over the president’s “style.” But the problem is the distinctly non-Christian substance of his values. Trump’s unapologetic materialism—his equation of financial and social success with human achievement and worth—is a negation of Christian teaching. His tribalism and hatred for “the other” stand in direct opposition to Jesus’s radical ethic of neighbor love. Trump’s strength-worship and contempt for “losers” smack more of Nietzsche than of Christ. Blessed are the proud. Blessed are the ruthless. Blessed are the shameless. Blessed are those who hunger and thirst after fame.

And yet, a credible case can be made that evangelical votes were a decisive factor in Trump’s improbable victory. Trump himself certainly acts as if he believes they were. Many individuals, causes, and groups that Trump pledged to champion have been swiftly sidelined or sacrificed during Trump’s brief presidency. The administration’s outreach to white evangelicals, however, has been utterly consistent.

Trump-allied religious leaders have found an open door at the White House—what Richard Land, the president of the Southern Evangelical Seminary, calls “unprecedented access.” In return, they have rallied behind the administration in its times of need. “Clearly, this Russian story is nonsense,” explains the mega-church pastor Paula White-Cain, who is not generally known as a legal or cybersecurity expert. Pastor David Jeremiah has compared Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump to Joseph and Mary: “It’s just like God to use a young Jewish couple to help Christians.” According to Jerry Falwell Jr., evangelicals have “found their dream president,” which says something about the current quality of evangelical dreams.

was joined one night at Madison Square Garden by none other than Martin Luther King Jr.

was joined one night at Madison Square Garden by none other than Martin Luther King Jr.Over time, evangelicalism got a revenge of sorts in its historical rivalry with liberal Christianity. Adherents of the latter gradually found better things to do with their Sundays than attend progressive services. In 1972, nearly 28 percent of the population belonged to mainline-Protestant churches. That figure is now well below 15 percent. Over those four decades, however, evangelicals held steady at roughly 25 percent of the public (though this share has recently declined). As its old theological rival faded—or, more accurately, collapsed—evangelical endurance felt a lot like momentum.

With the return of this greater institutional self-confidence, evangelicals might have expected to play a larger role in determining cultural norms and standards. But their hopes ran smack into the sexual revolution, along with other rapid social changes. The Moral Majority appeared at about the same time that the actual majority was more and more comfortable with divorce and couples living together out of wedlock. Evangelicals experienced the power of growing numbers and healthy subcultural institutions even as elite institutions—from universities to courts to Hollywood—were decisively rejecting traditional ideals.

As a result, the primary evangelical political narrative is adversarial, an angry tale about the aggression of evangelicalism’s cultural rivals. In a remarkably free country, many evangelicals view their rights as fragile, their institutions as threatened, and their dignity as assailed. The single largest religious demographic in the United States—representing about half the Republican political coalition—sees itself as a besieged and disrespected minority. In this way, evangelicals have become simultaneously more engaged and more alienated.

The overall political disposition of evangelical politics has remained decidedly conservative, and also decidedly reactive. After shamefully sitting out (or even opposing) the civil-rights movement, white evangelicals became activated on a limited range of issues. They defended Christian schools against regulation during Jimmy Carter’s administration. They fought against Supreme Court decisions that put tight restrictions on school prayer and removed many state limits on abortion. The sociologist Nathan Glazer describes such efforts as a “defensive offensive”—a kind of morally indignant pushback against a modern world that, in evangelicals’ view, had grown hostile and oppressive.

This attitude was happily exploited by the modern GOP. Evangelicals who were alienated by the pro-choice secularism of Democratic presidential nominees were effectively courted to join the Reagan coalition. “I know that you can’t endorse me,” Reagan told an evangelical conference in 1980, “but I only brought that up because I want you to know that I endorse you.” In contrast, during his presidential run four years later, Walter Mondale warned of “radical preachers,” and his running mate, Geraldine Ferraro, denounced the “extremists who control the Republican Party.” By attacking evangelicals, the Democratic Party left them with a relatively easy partisan choice.

recent survey by Barna, a Christian research firm, more than half of churchgoing Christian teens believe that “the church seems to reject much of what science tells us about the world.” This may be one reason that, in America, the youngest age cohorts are the least religiously affiliated, which will change the nation’s baseline of religiosity over time. More than a third of Millennials say they are unaffiliated with any faith, up 10 points since 2007. Count this as an ironic achievement of religious conservatives: an overall decline in identification with religion itself.

recent survey by Barna, a Christian research firm, more than half of churchgoing Christian teens believe that “the church seems to reject much of what science tells us about the world.” This may be one reason that, in America, the youngest age cohorts are the least religiously affiliated, which will change the nation’s baseline of religiosity over time. More than a third of Millennials say they are unaffiliated with any faith, up 10 points since 2007. Count this as an ironic achievement of religious conservatives: an overall decline in identification with religion itself.By the turn of the millennium, many, including myself, were convinced that religious conservatism was fading as a political force. Its outsize leaders were aging and passing. Its institutions seemed to be declining in profile and influence. Bush’s 2000 campaign attempted to appeal to religious voters on a new basis. “Compassionate conservatism” was designed to be a policy application of Catholic social thought—an attempt to serve the poor, homeless, and addicted by catalyzing the work of private and religious nonprofits. The effort was sincere but eventually undermined by congressional-Republican resistance and eclipsed by global crisis. Still, I believed that the old evangelical model of social engagement was exhausted, and that something more positive and principled was in the offing.

I was wrong. In fact, evangelicals would prove highly vulnerable to a message of resentful, declinist populism. Donald Trump could almost have been echoing the apocalyptic warnings of Metaxas and Graham when he declared, “Our country’s going to hell.” Or: “We haven’t seen anything like this, the carnage all over the world.” Given Trump’s general level of religious knowledge, he likely had no idea that he was adapting premillennialism to populism. But when the candidate talked of an America in decline and headed toward destruction, which could be returned to greatness only by recovering the certainties of the past, he was strumming resonant chords of evangelical conviction.

Trump consistently depicts evangelicals as they depict themselves: a mistreated minority, in need of a defender who plays by worldly rules. Christianity is “under siege,” Trump told a Liberty University audience. “Relish the opportunity to be an outsider,” he added at a later date: “Embrace the label.” Protecting Christianity, Trump essentially argues, is a job for a bully.

ceased to describe himself as an evangelical even as he exemplifies the very best of the word.

ceased to describe himself as an evangelical even as he exemplifies the very best of the word.Evangelicalism is hardly a monolithic movement. All of the above leaders would attest that a significant generational shift is occurring: Younger evangelicals are less prone to political divisiveness and bitterness and more concerned with social justice. (In a poll last summer, nearly half of white evangelicals born since 1964 expressed support for gay marriage.) Evangelicals remain essential to political coalitions advocating prison reform and supporting American global-health initiatives, particularly on aids and malaria. They do good work in the world through relief organizations such as World Vision and Samaritan’s Purse (an admirable relief organization of which Franklin Graham is the president and CEO). They perform countless acts of love and compassion that make local communities more just and generous.

All of this is arguably a strong foundation for evangelical recovery. But it would be a mistake to regard the problem as limited to a few irresponsible leaders. Those leaders represent a clear majority of the movement, which remains the most loyal element of the Trump coalition. Evangelicals are broadly eager to act as Trump’s shield and sword. They are his army of enablers.

It is the strangest story: how so many evangelicals lost their interest in decency, and how a religious tradition called by grace became defined by resentment. This is bad for America, because religion, properly viewed and applied, is essential to the country’s public life. The old “one-bloodism” of Christian anthropology—the belief in the intrinsic and equal value of all human lives—has driven centuries of compassionate service and social reform. Religion can be the carrier of conscience. It can motivate sacrifice for the common good. It can reinforce the nobility of the political enterprise. It can combat dehumanization and elevate the goals and ideals of public life.

/media/video/upload/0418_WEL_Gerson_Lead-optimized_(2).mp4) April 2018 Issue

April 2018 Issue